Energy Panic

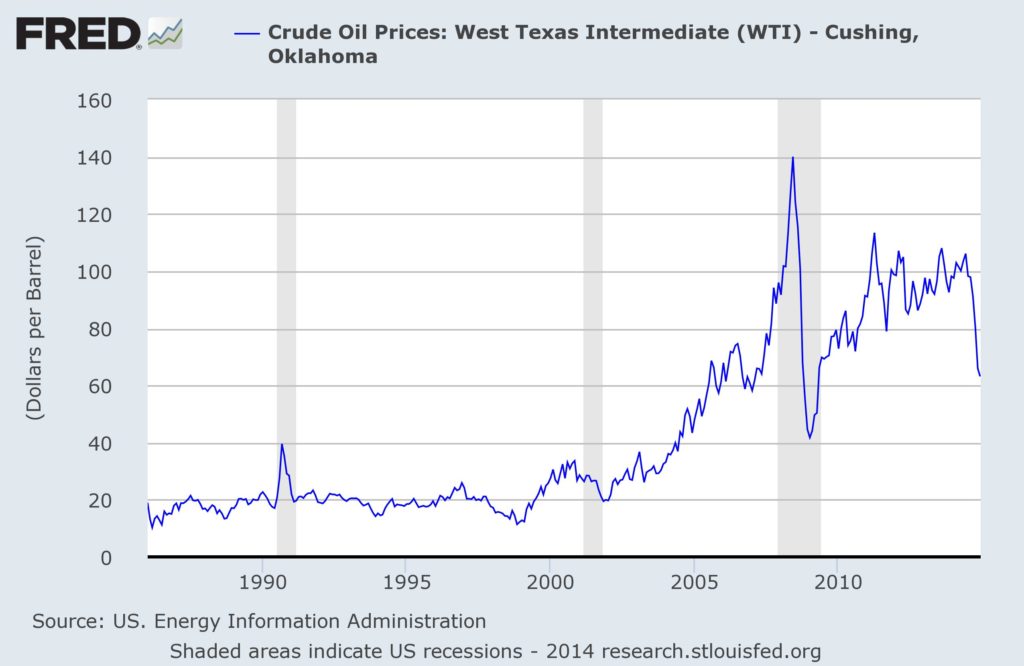

Take a look at the price of a barrel of good ol’ West Texas Intermediate (see graph below). Two things jump out at me: big declines occur in recessions (which makes sense as demand falls), and there’s a fair amount of fluctuation all the time. The recent 50% drop is unusual in that it has not occurred during a recession (unless we’re in one now and don’t know it; but I don’t think so). So, why has the price of oil fallen so dramatically? And what else has been impacted by this plunge? And how should investors think about opportunities in the energy sector? Well, a full answer requires more space than this blog allows, but I’ll try to hit the highlights.

As I noted two weeks ago (here and here), this is a supply-driven price decline, not a demand-driven one. The Saudis simply decided to stop acting as the swing producer, as they have for the past 40 years, thereby allowing a glut of oil to develop in the world markets. So, far from signaling a global recession, the drop in crude will boost the wealth of consumers (at the expense of oil producers).

The effect has not been limited to the commodity: oil-sensitive assets have sold-off as dramatically. The Russian ruble has lost half its value (see chart below), and credit spreads for high-yield energy companies have blown out (see second chart).

Yesterday, Russia raised its overnight rate from 10.5% to 17% in an attempt to stem the sell-off of the ruble. The last time such a dramatic action was taken was in 1998 when Russia eventually defaulted (admittedly, that was a much more dramatic episode: the overnight rate went to 150% before the entire system collapsed).

I am not an advocate of stepping in front of moving trains (or catching falling knives…choose your metaphor). I don’t know where or when the bottom is for oil, but I’m pretty sure the energy cycle (like the commodity cycle, the business cycle, the economic cycle, the bi-cycle…sorry) is alive and well. Oil didn’t go up forever (as was the consensus view in 2007, 1989, et. al.), and it will not go to zero (at least it won’t stay there for long). But I’d rather invest in projects that assume oil at $55 rather than at $110.

I don’t have a view on timing of oil prices, but I do have a concern at a potential repeat of a previous policy mistake. Following the collapse of the hedge fund, Long Term Capital Management and the subsequent Russian default in late 1998, central bankers flooded the markets with excess liquidity. That liquidity found its way in to a very small segment of the equity markets, the so-called “dot-com” companies, creating the following year perhaps the most excessive valuations ever seen in US equities.

As I said last week, a decline in the price of oil (or any other good or commodity) is not a monetary event, it does not cause deflation. It is strictly a wealth transfer from oil producers to consumers. The Fed should be careful about misinterpreting the effects of an oil price decline, and avoid over-stimulating an economy that is kicking into a higher gear already.