Europe Sputters, US Cruises

Europe’s unemployment rate is 11.5%. Europe is currently growing at less than 1%. A rule of thumb is that it takes excess growth of 2-2.5% to drop the unemployment rate by 1%. I think you see the problem. This is not advanced math.

Mario Draghi, head of the European Central Bank (ECB), would like to juice the economy with some monetary stimulus, but he’s finding that there is a gap between what he would like, what the Germans would like, and what can actually be done.

In the midst of the barrage of news about plunging oil prices and winter storms, you may have missed last week’s party held by the European Central Bank (ECB) where all the Eurozone banks were invited to attend to grab free money. A similar party was held in September, and between the two auctions, up to 400 billion euros were made available to banks. The idea was to give banks 3-year loans at essentially no cost, and banks would then lend these funds to European companies and households, earning a nice spread for the banks and boosting the region’s economy. Nice in theory, but banks declined to take their full allotment, taking down just 212 billion. Banks in the periphery countries drew all they could to bolster their weak balance sheets, but banks in the core countries took only about one-third of the funds that were offered, citing a lack of funding constraints as the primary reason for declining more funds, with poor loan growth as a secondary consideration. In other words, the banks said to the ECB, “we don’t want your money, we have more than we need.”

So an attempt to inject liquidity into the financial system fell way short of expectations, leaving Europe with both a growth rate and an inflation rate less than 1%. At these rates, the debt burden continues to grow for most countries. What is a central banker to do?

The ECB is currently buying asset-backed securities (ABS), but this is a relatively small market, and is having little impact. There is talk of buying sovereign bonds, as the Fed and the Bank of England have done, but this is highly uncertain: to begin with, there are no European sovereign bonds, only the bonds of member countries. So, which bonds will the ECB buy? German bunds yielding less than 1%? to what purpose? Greek national bonds? Really? Even assuming the ECB has the legal mandate to do so (which it doesn’t: it is prohibited by its charter from buying the sovereign bonds of member countries), under what conditions and criteria, and how much and in what proportion of bonds would they buy? These questions have no answers yet.

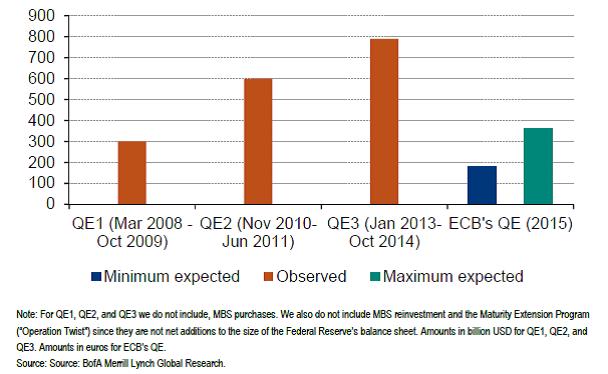

The Fed, in three rounds of quantitative easing (QE) purchased about $1.4 trillion of bonds, whereas the ECB, through various programs, is expected to buy no more than 350 million euros (see chart below). Even assuming it can execute this (far from a given), will it have any impact?

It is highly controversial among economists as to the effect Quantitative Easing has on an economy. Proponents argue it adds needed liquidity to keep the financial system afloat, thus enabling an economy to repair its balance sheet with minimizing dislocations. Critics believe it only serves to enlarge the presence and influence of the central bank by expanding its balance sheet, setting the economy up for more pain down the road when that balance sheet must contract.

My own two cents (which may not even be worth a penny), is a third perspective: QE has had no meaningful impact on the real economy, but it has served as notice that the central bank is ready, willing and able to provide unlimited liquidity to the financial system, thus eliminating the concern of a systemic default. This signal has some value.

Unfortunately, the poor results at last week’s TLTRO (Targeted Longer Term Refinancing Operation) signal the impotence of the ECB. Rather than boosting confidence, the ECB reinforced concerns that it might not have the tools or process to avoid or reverse a potential systemic default. I’m not suggesting one is imminent, or even likely, just that Europe faces many structural hurdles, among them, the efficacy of its central bank.

Meanwhile, the US data point to accelerating strength. Last week, retail sales were especially strong, and this morning, industrial production is just smoking. Production jumped 1.7% in November, the fastest monthly gain since 2010, and is up 5.2% over the past 12 months. Capacity Utilization rose to 80.1%, the highest level in nearly 7 years. A tale of two regions, indeed.