Laboring

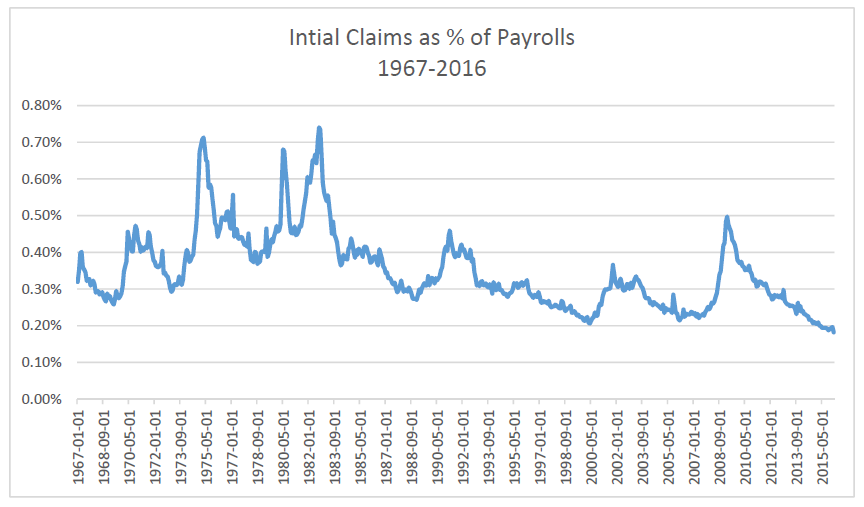

In some respects, this is a golden age for labor. The unemployment rate has dropped to 4.9% from a high of 10% in October 2009. It’s not quite as low as the 3.8% in early 2000, or the post-war low of 2.5% in 1953, but it’s pretty close to full employment. The broadest measure of unemployment (U-6, which includes discouraged as well as part-time workers who would like full-time jobs) is somewhat elevated, but has fallen sharply to 9.7%, from a high of 17.1%. 143 million Americans are employed, the most ever. The average wage is over $25/hour, also the highest ever. Initial claims for unemployment benefits is just 0.18% of payrolls, the lowest on record (graph below).

To be sure, there are pockets of concern. Growth in wages has been modestly accelerating, but is still very low in historical terms, 2.2% over the past year. Low wage growth doesn’t surprise me, though, as it is consistent with the very low productivity gains we’ve seen in this recovery. Raising productivity is the key to long-term improvement in the standard of living, and there is much debate about how to accomplish this. Some, notably Robert Gordon of Northwestern, argue that productivity gains are in the past, not to be seen again. I believe he’s wrong, but I admit that’s more an article of faith than I can support with hard evidence, for now.

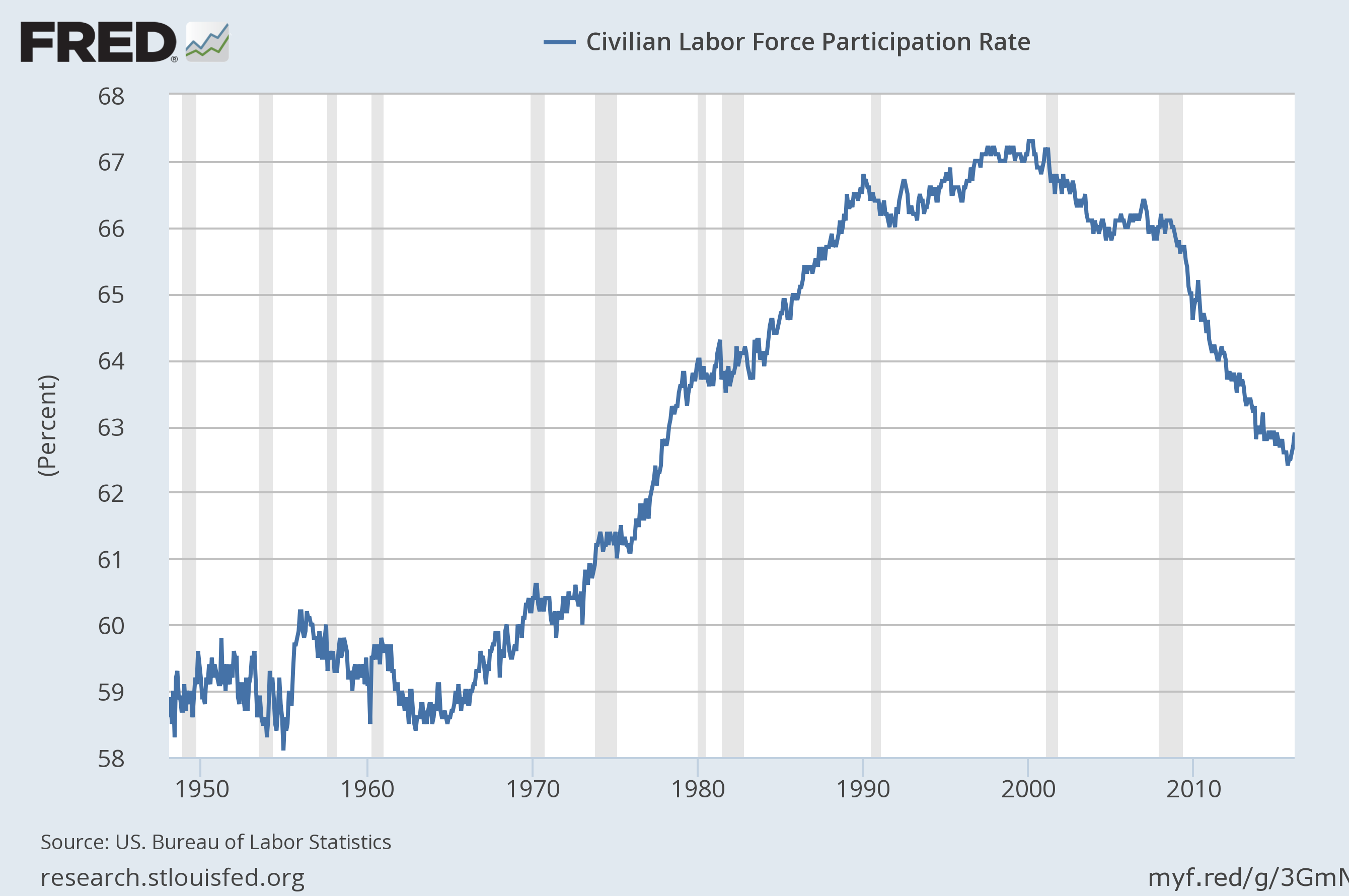

Beyond low productivity growth, the other structural concern I have is the labor participation rate. More than 67% of working age adults were working in 2000, dipping to 66% on the cusp of the 2008 recession. Today, less than 63% are employed (graph below).

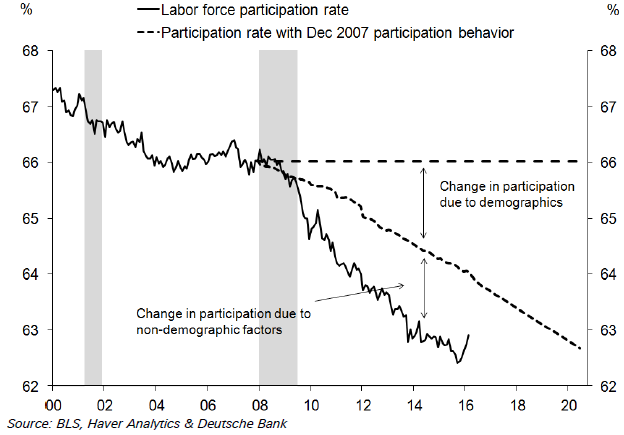

Demographics explain a lot of this decline. The estimate below shows a “natural” decline in the participation rate to around 64% due to aging, with the remaining +1% explained by other factors. Those factors include rising disability, more education and the business cycle.

The rise in disability is poorly understood: jobs have become less dangerous as they’ve become less physical, so why would disability rolls be rising? Perhaps there has been an increase in non-physical disability, or the qualifications have been relaxed, or the aging workforce is more susceptible to disability, or all of the above or more. We do know that younger people are staying in school longer, as the participation rate fell sharply over the past 8 years for those under age 25, from 59.2% to 55.5%. Interestingly, the participation rate for workers over age 55 increased from 38.9% to 40.1% over this recent period. Lastly, the business cycle influences the participation rate. In the past 5 months, September 2015 to February 2016, as the economic recovery continued, the labor force expanded by 2.02 million workers. All, plus a few more, found jobs.

So, there’s a lot of good news on the labor front. But the long-term, let’s call it the “structural,” trend in the participation rate is likely to head lower due to demographic factors, capping the potential output of the economy. Coupled with low productivity growth, our national wealth will likely accrete at a slower pace than in the past.