Mauled

Investors in Emerging Markets could be forgiven for feeling as if they’ve gone 15 rounds with Ronda Rousey (see below). Or, more like 3 years with the the best pound-for-pound fighter today (she might even give Sugar Ray Robinson, who gets my vote for best of all-time, a contest). It’s been brutal.

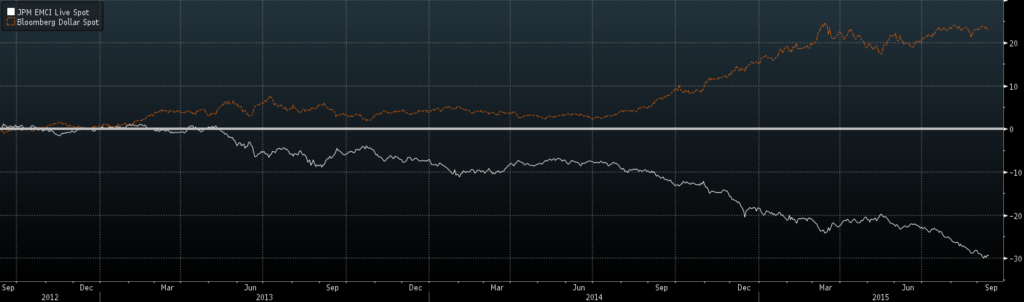

How brutal, you ask? EM currencies have dropped 30% in the past 3 years, while the US$ has jumped more than 20% (see first graph below). This has translated into an overall 10% decline in EM equities, 40% behind global equities and more than 50% below the return of US stocks (second graph below, showing last 3-year performance of US, World and EM equities).

Unlike the UFC, no bell will ring for investors announcing the end of the carnage. And only a fool would pretend to know when that will happen.

Markets can be (and often are) irrational at moments, but over time, there are usually good reasons for how assets perform. There are valid reasons for the pummeling of emerging market assets. Growth rates have slowed considerably, both absolutely as well as relative to developed economies. Earnings are still being revised lower. Many of the countries remain highly dependent on commodity extraction, at a time when commodity prices are down 50% and we are likely entering a multi-decade period of little price appreciation. Institutional governance—political, economic and social—is immature (I’m being polite: corruption pervades many societies). There are very few obvious silver linings here.

Still, while things could very likely get even worse for EM investors, the degree of damage has already been pretty extreme. The last big, global EM crisis was in 1997-98, when the Thai baht devalued by 90%, dragging other East Asian currencies lower, and culminating in a Russian default on its debt. That scenario is very unlikely today for two primary reasons. First, most currencies float today, thus the adjustments needed can (and do) occur in due course, rather than precipitously, as was the case in 1997-98. Secondly, most EM countries today run either surpluses or small current account deficits, and total debt-to-GDP is generally modest (China and Malaysia are exceptions). Gross external debt-to-FX reserves is one-quarter the level of 1997 (again, there are exceptions, with Brazil and Turkey seen as more vulnerable). The severe economic pressures that caused markets to collapse in 1997 are not just present today.

So while conditions have been bad, and prospects seem bleak, the markets have (mostly, appropriately) adjusted. This is not an argument to buy EM now, only to acknowledge that much of the losses have been already been realized which, in itself, mitigates the likelihood of a sudden crisis.

One round, or 15 rounds, with Ronda Rousey cannot be a pleasant experience. But investors have hung in this long, and one day, the bell will ring.