Money Matters

When the Fed embarked on Quantitative Easing (QE), many prominent economists warned this would lead to hyperinflation (or, at least, an wanted surge in inflation). Didn’t happen. With QE ended, many economists (mostly different, but some, amazingly, the same), warn that deflation will soon engulf us, leading to economic ruin.

One lesson to take from these public debates is that it is usually best to ignore predictions (especially about the future, and maybe especially from economists). But really, especially predictions that are based on theory that then do not conform with the empirical facts.

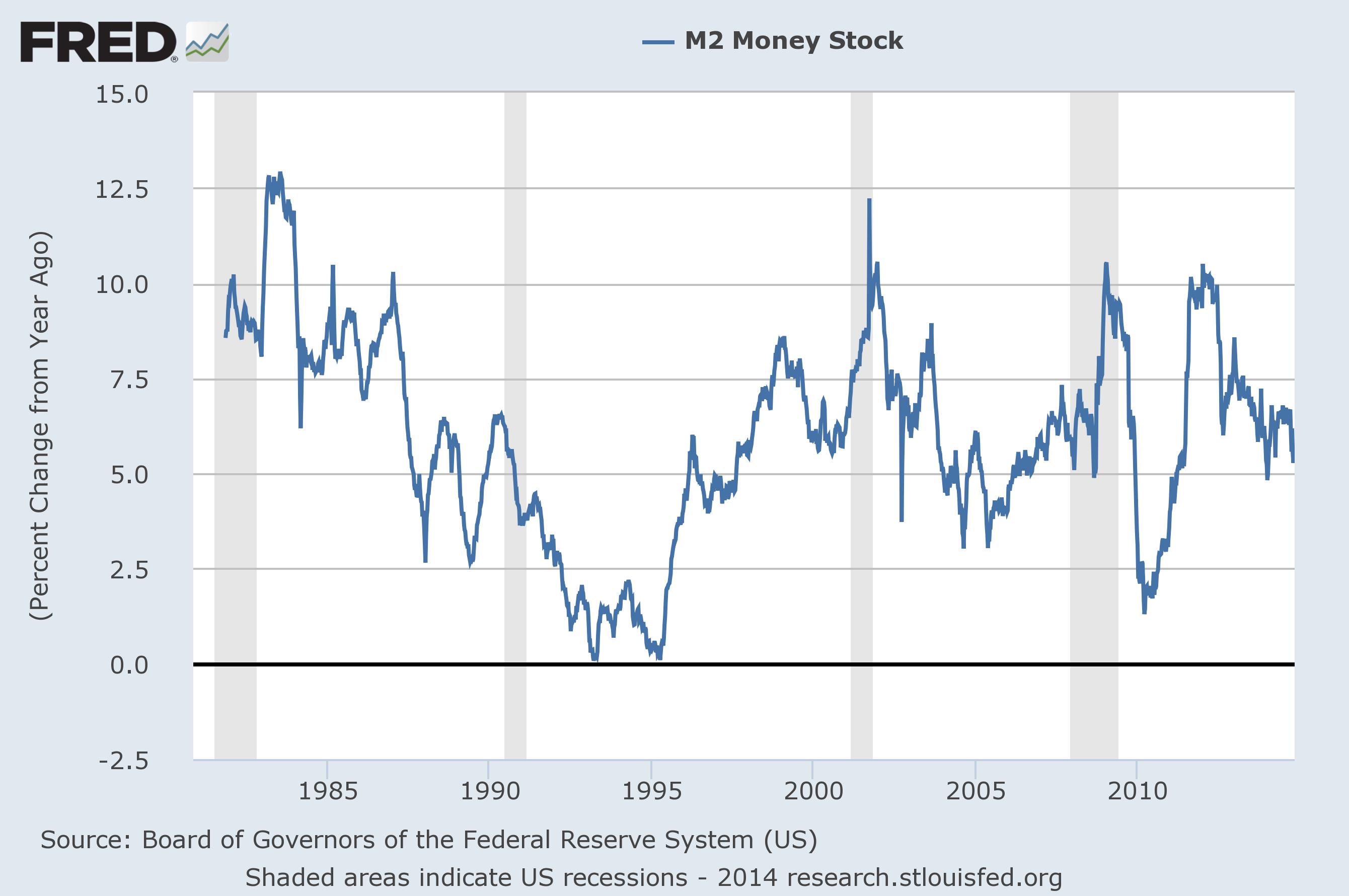

This first chart shows the growth of money supply (M2) in the US over the past 35 years. As you can see, money growth fell below 2.5% following the recession, bounced back strongly to 10%, and has settled in around 5-6% (5.3% at the latest reading). Not coincidentally, nominal US GDP growth was most recently 3.5% (real) plus 1.7% (inflation) or 5.2%. By maintaining solid growth in money supply, the Fed has ensured solid nominal GDP growth. Also, note that money supply growth has reverted to its long-term mean over the past through years despite the introduction and withdrawal of three and one-half (including Operation Twist here) of QE programs, meaning it’s hard to see any real world impact of QE (on either side).

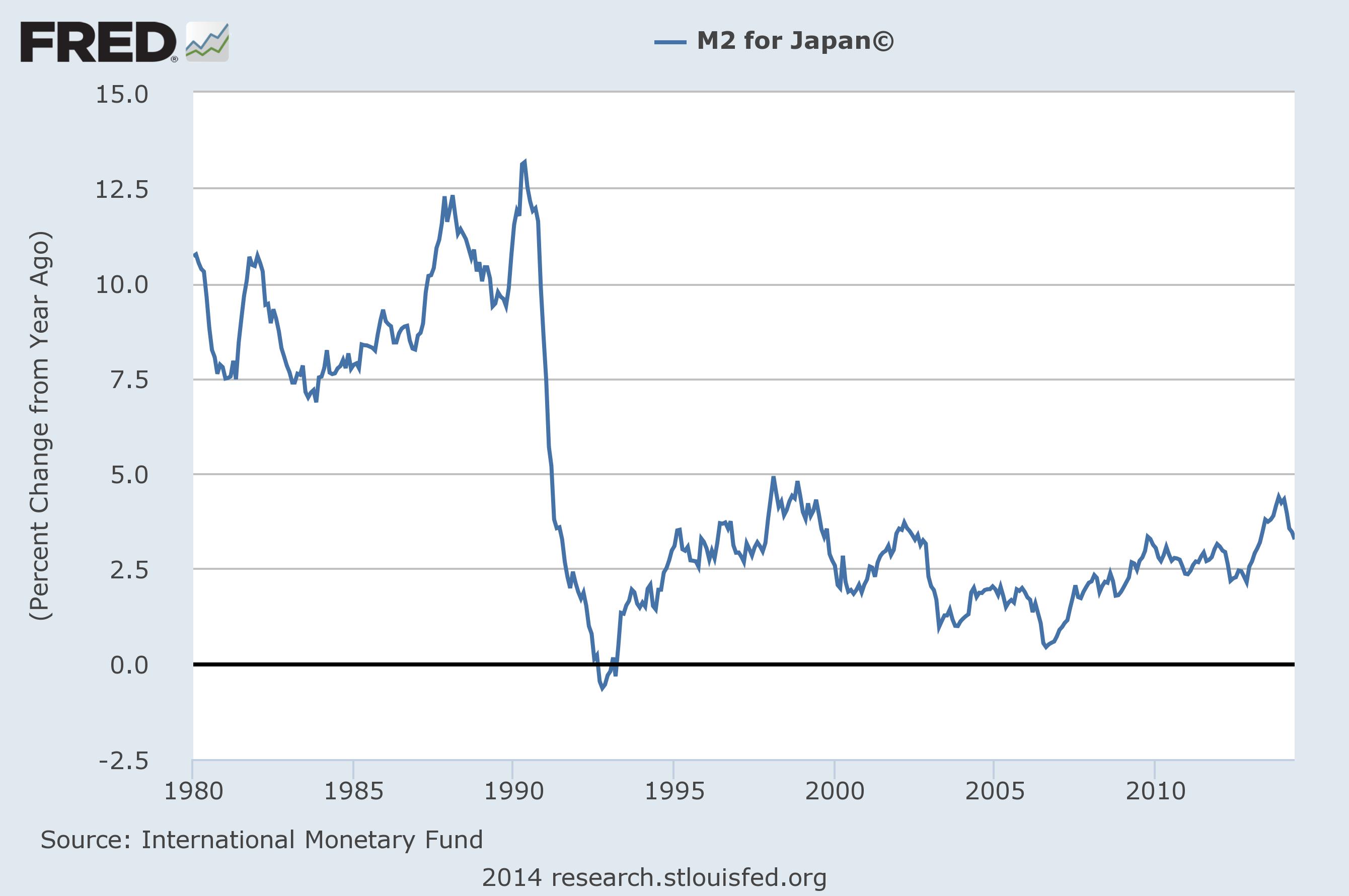

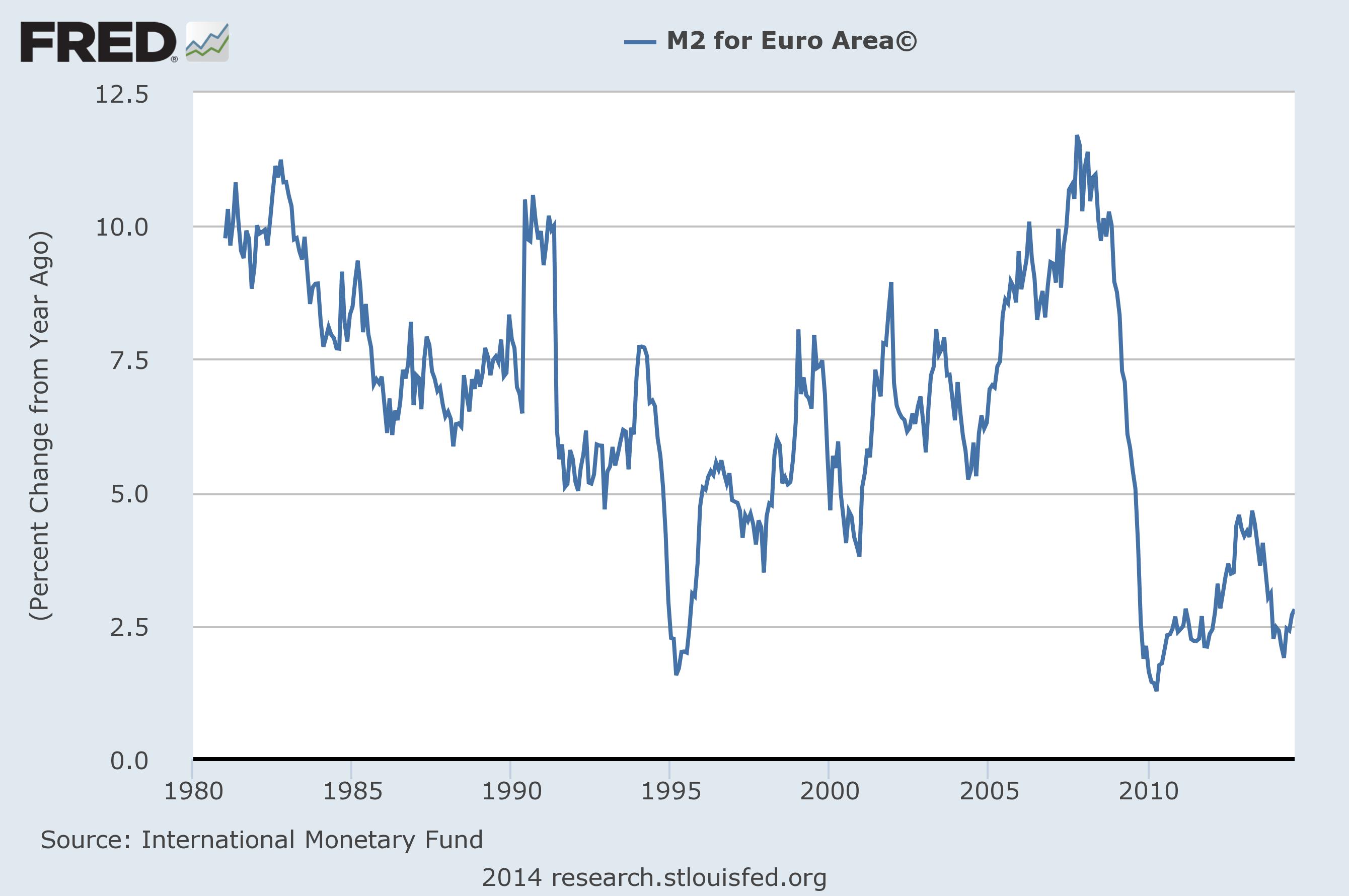

Compare and contrast with the central banks of Japan and Europe (see charts below). The Bank of Japan has kept money growth between 0% and 5% for the past 20 years (most recent: 3.5%). The European Central Bank has been all over the map, between 1% and 11% over the past 30 years, but hovering around 2.5% over the past 5 years (3% in the latest data).

Money growth tells the stories of the economies: that US economic growth has been moderate, while Japan and Europe have stagnated. Money growth also dictates the path of the price level, since inflation (and deflation) are always and everywhere a function of the supply of money (as Milton Friedman pointed out). The anemic growth in money supply in Japan and Europe means there is an elevated risk of deflation (although still not a likely outcome if money growth can remain positive). In the US, 5-6% money growth is about just right: fast enough where deflation risks are minimal, and not too fast to stoke much higher inflation.