Path to Progress

Zimbabwe is a country of 14 million people. I’ve never been there, and I can’t recall if I’ve ever met anyone from there, but I’m sure that the vast majority of Zimbabweans are very pleasant people. I’ll also stipulate that the vast majority are hard-working, although that may be difficult to prove. Of the 14 million people in the country, just 700,000 are considered officially employed.

I’m not sure what the other 13,300,000 people are doing every day, but this astonishing fact highlights for me the depth of the challenge for so many countries. Perhaps few are as abject failures as Zimbabwe, but it should be crystal clear, after three-quarters of a century of experimentation around the globe, that political choices matter.

Respect for the rule of law, reasonable regulations, open economies that are forced to compete globally: these are clear factors that lead to progress, which I’ll define as improved living standards for the majority of citizens. That’s it: these are the only three necessary and sufficient conditions for progress.

Notable is long list of items neither necessary nor sufficient for progress: foreign aid, abundant natural resources, a highly educated population, and so many others. Zimbabwe may be particularly cursed with a long-running kleptocracy that funnels the meager wealth of the country to a handful of Mugabe (see photo below) family and friends, but for many countries, there will simply be no progress unless they embrace these three principles.

Statistics like the one above, where just 5% of a population is officially employed, serve to illustrate the impossibility of progress without radical political change for many countries. That is, poor economic choices manifest first in the economies, but often spread to infect political and social structures. Tinkering with a little more aid or debt restructuring will not ameliorate the systemic dry rot that erodes the foundations of these societies.

Africa, sadly, contains dozens more examples of bad economic policies and pervasive political and social corruption. In the Western Hemisphere, Cubans are poorer today, in absolute terms, as well in relative terms, than they were in 1958, when Castro came to power. A century ago, Argentina had the same GDP as the United States; today, it is less than 1/30th of the US. In Venezuela, inflation is currently running at around 200%, just one (albeit dramatic) consequence of nearly two decades of ruinous policies instituted first by Hugo Chavez and, upon his death, by his deputy, Nicolas Maduro. Venezuela’s collapse was inevitable with Chavez’ policies, just delayed when oil prices were above $100/barrel.

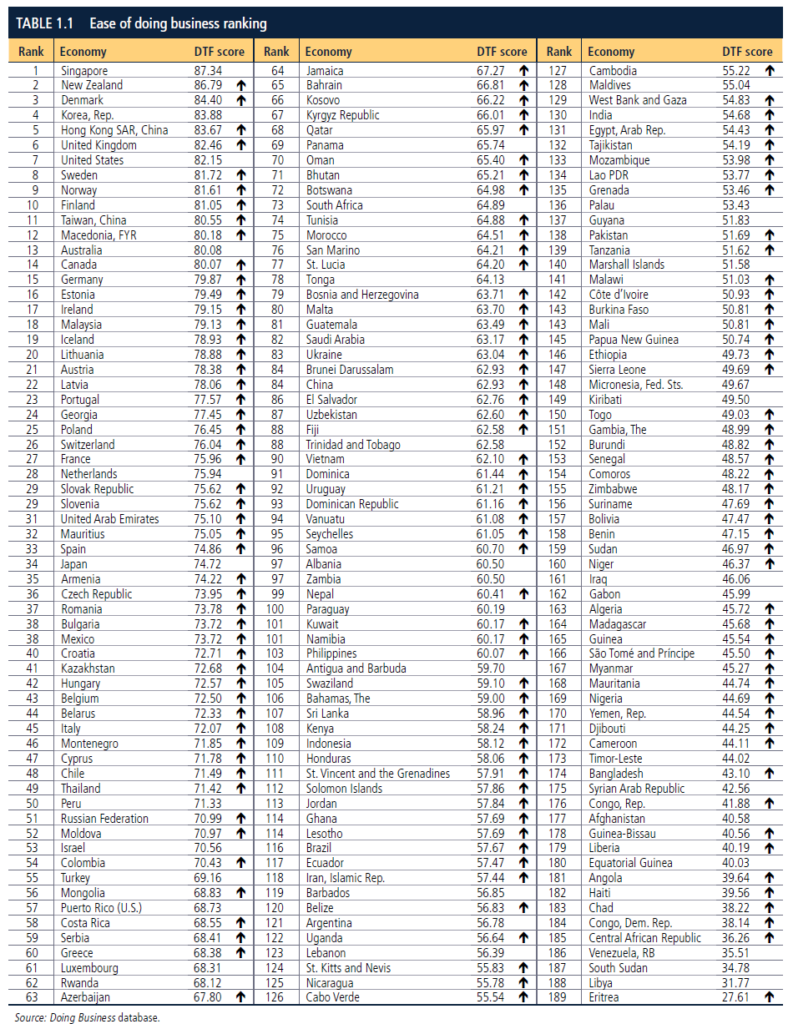

India is every investor’s favorite emerging country today, with some justification: a new Prime Minister with a history of pro-business initiatives and a new Central Bank chairman who was a distinguished economist at the University of Chicago. But let’s remember the economic morass that is India, with a bureaucracy that makes the Byzantine’s seem streamlined. Amazingly, it’s easier to start a business in Gaza than in India (World Bank—see table).

It’s certainly anecdotal, but I was struck by a headline a few months ago (in the FT, which I take as credible) that the state government of Uttar Pradesh advertised for 328 entry-level job openings, including guards and tea boys (which I assume means serving tea to higher ranking bureaucrats, although I’m not sure why they can’t get their own tea). Now, the official unemployment rate in India is 5%. Uttar Pradesh received 2.32 million applications for these 328 positions. If, somehow, the state could interview 2,000 applicants per day, it would take over four years to get through everyone. You could argue that India has a lot of low-skilled workers, thus accounting for the deluge of applicants. But Uttar Pradesh also advertised for a few positions as messengers, requiring five years of education (that is, had to have completed 5th grade) and an ability to ride a bicycle. It received 25,000 applicants with master’s degrees, 255 holding Ph.Ds. Salaries start at Rs16,000/month (about $240) if you’d like to add your resume to the pile.

I suppose the point of all this is that I think about investing in some countries differently than I do in others. The usual rules of valuation, growth, profitability apply to countries with well-established rules and institutions and open economies. Where those are not present, other criteria become more important. This is not an argument to avoid investing in emerging markets, but to understand the deeper, structural issues each country faces.

In the past week, voters in Venezuela finally said Basta! (enough!) to the ineptitude of the Chavez/Maduro regime. And voters in Argentina said the same to the disastrous policies of the Peronistas. After decades of ruinous policies in both countries, these are small steps forward: small, but forward.

Zimbabwe may have to wait for Mugabe to die (which won’t come soon enough), but progress there and elsewhere will only happen when these countries embrace the rule of law, impose reasonable regulations, and insist businesses compete to world standards. If my message to investors is to be careful, the message to these countries is optimistic and straightforward: the path to progress is well-known and well-proven. It’s a bit of a mystery, and a shame, that so many countries have chosen to follow other paths.