Pressure Building

Yes, we all know the European economy is not growing: stagnant, sclerotic, etc. But this fact is not a crisis. It’s a concern, a problem, a challenge, but not a crisis.

It is hard to get politicians to act (a global observations, not just in Europe or the US), harder to get them to act in ways that actually benefit the economy, and nearly impossible to get them to favor the long-term if it involves pain in the short-term (I’m using short-term and long-term as defined by the election cycle: short-term is before the next election, long-term is afterward). Unless there is a clear and present danger; there’s nothing like a crisis to focus the mind. In early 2012, there was much (and serious) talk of multiple sovereign defaults in Europe, the break-up of the euro, all leading to the collapse of European social order. The then newly-appointed head of the ECB, Mario Draghi, broke with his predecessor (Jean-Clause Trichet, the dour Frenchman who acted as the Bundesbank’s spokesman), and certainly did not consult with Chancellor Merkel when he announced the ECB would do “whatever it takes” to ensure currency stability in the Eurozone. That helped: markets re-priced sovereign default from near certainty (Greece) to low probability. Crisis averted.

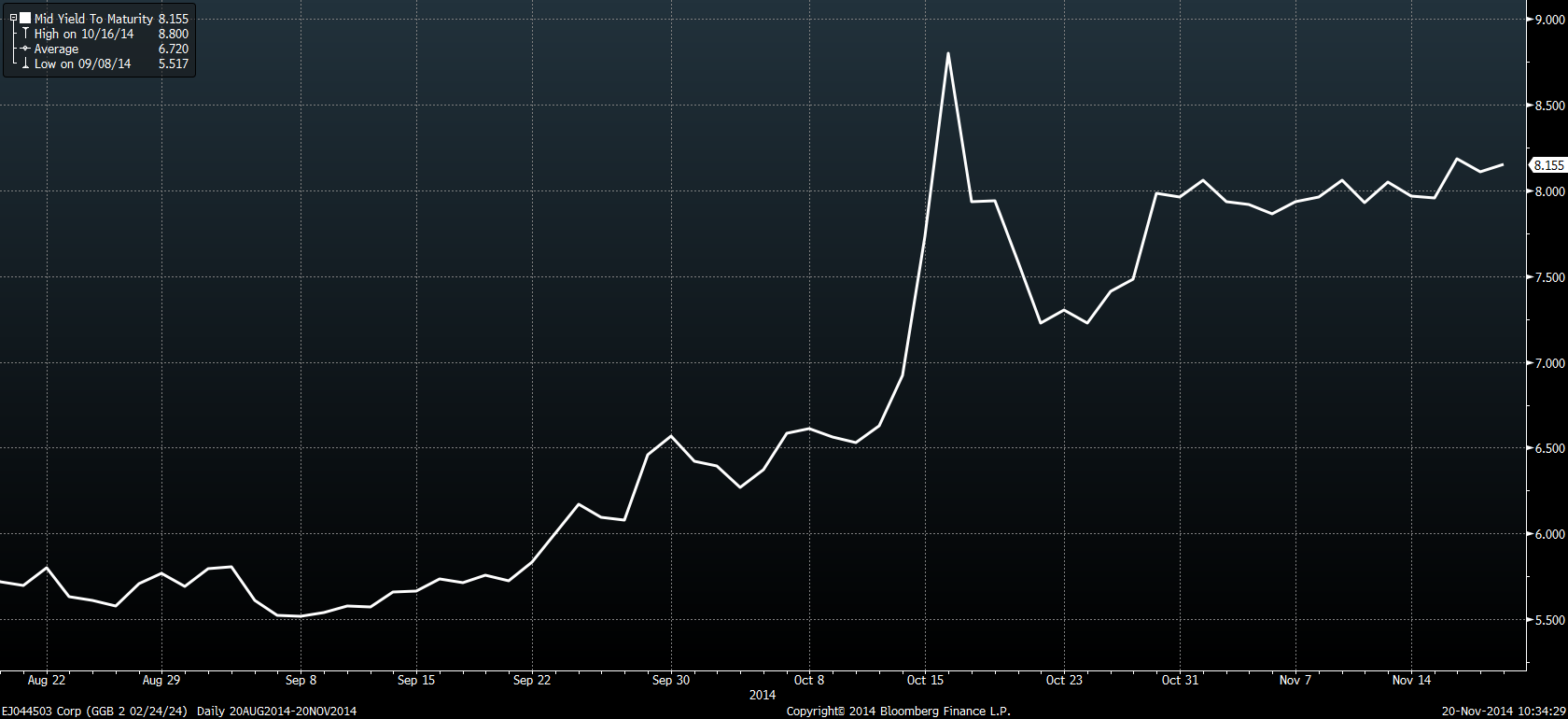

Well, the crisis was averted, but not the problem (or challenge, if you prefer). Smarter minds and more powerful computers than I have continually assess the probabilities of multiple outcomes in the capital markets, but here’s a very simple rule of thumb that captures most of what is important: if the nominal growth of an economy is greater than the nominal interest rate a country borrows at, all will eventually work out. The relationship is flipped, that country has a problem. Houston (I mean, Greece), you have a problem. Greece’s nominal GDP growth is around 1% (yes, that makes it one of the stronger economies in the Eurozone). But, as the chart below shows, over the past 2 months, the cost of borrowing rose from 5.5% to over 8%. So, in simple math, if Greece can grow at 1% but has to borrow at 8%, its debt will continue to grow 7% per year. Now, this calculation is only a guide, not an axiom, but it highlights 2 points: without even modest growth, Greece was continuing to sink into a deeper debt hole. Secondly, with the spike in yields, it is now sinking faster and deeper.

The Greek economy has shrunk more than 20% over the past few years, its official unemployment rate is over 25%, Greek equities are down 30% this year, and its budget deficit is still 3% of GDP (an improvement, but the sign is still negative, so the debt builds). Even with a planned cash injection next month, it will run out of cash mid-next year. More loan assistance is possible, which will postpone the crunch another year, but it’s just kicking a can without some economic growth.

This is no longer a mere problem for European politicians, it is now a crisis. But I’m not sure they know it yet.