Rupture

[nota bene: this is a long one; if you don’t have time, just skip to the summary at the end. I promise, no hard feelings.]

The political experts were remarkably accurate in last week’s UK referendum on continuing to remain in the European Union, projecting a vote of 52%/48%. The actual final tally was 51.9% to 48.1%, so chalk one up to the pundits.

Well, the numbers were spot on, but the sign was the wrong way: instead of a narrow victory to remain, the voters chose to exit. The Bloomsbury Crowd [a group of Cambridge-educated intellectuals who gathered in Bloomsbury, London in the early part of the 20th century to discuss and affirm the importance of themselves] was shocked (shocked!).

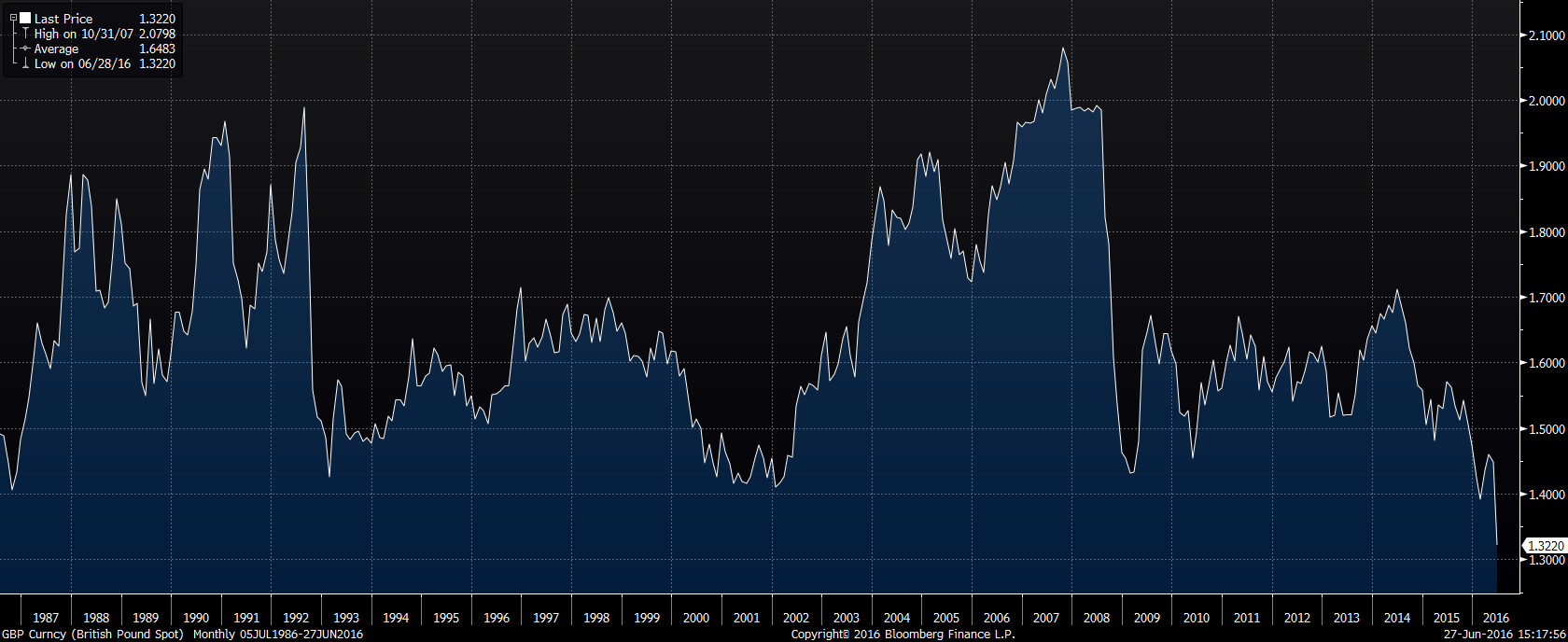

This political earthquake sent tremors throughout the markets. The pound sterling saw its biggest single day decline since exchange rates were floated in 1971, plummeting from 1.50 to 1.33 Friday, its lowest level since 1984 (see graph below, GBP/USD 1987-2016). Stocks plunged, gold surged and government bond yields fell from minuscule to imperceptible levels, all as investors shunned risk and sought safety. Economists were quick to re-run their DSGE models (Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium, but you probably already knew that), and shaved a few points off of UK GDP growth. S&P and Fitch promptly downgraded the country’s credit rating from AAA to AA.

GBP/USD, 1987-2016

The immediate impact of an earthquake is physical, but the repercussions are also psychological and economic. From my perspective, the Brexit (Britain exit) vote should be viewed from three angles: economic, financial and political.

Economic

Most economists cut their GDP forecasts in the UK by around 1.25% (some higher, some lower), and by about 0.5% for the EU and 0.25% for the US. The general assumptions are that trade barriers will rise and consumer and business spending will be curtailed to varying degrees. These economists are all very smart, and their forecasts may turn out to be true (although it’s been noted that economic forecasts make astrologers look prescient). Eschewing my DSGE model for the Magic 8 ball I had as a kid, my best guess at this point is that these economists are unduly pessimistic, at least in the near-term. The world economy, and especially Europe’s, is, and has been, facing strong headwinds of growth and productivity that has little or nothing to do with whether the UK stays or leaves the EU. In other words, I don’t see economic growth as hinging on Brexit.

Financial

The financial impact has been swift and severe, but utterly rational, in my view. Markets have sold assets in-line with their sensitivities to the UK and European economies. The currencies were the first to fall, and markets have generally distinguished between those assets with more and less exposure to the UK/Europe. The sell-off in equities has not been wholesale, and the indiscriminate selling that characterizes panic has not (yet, anyway) transpired. Stocks with greater exposure to the UK have fallen more than those with little or no exposure to that market, and that makes sense.

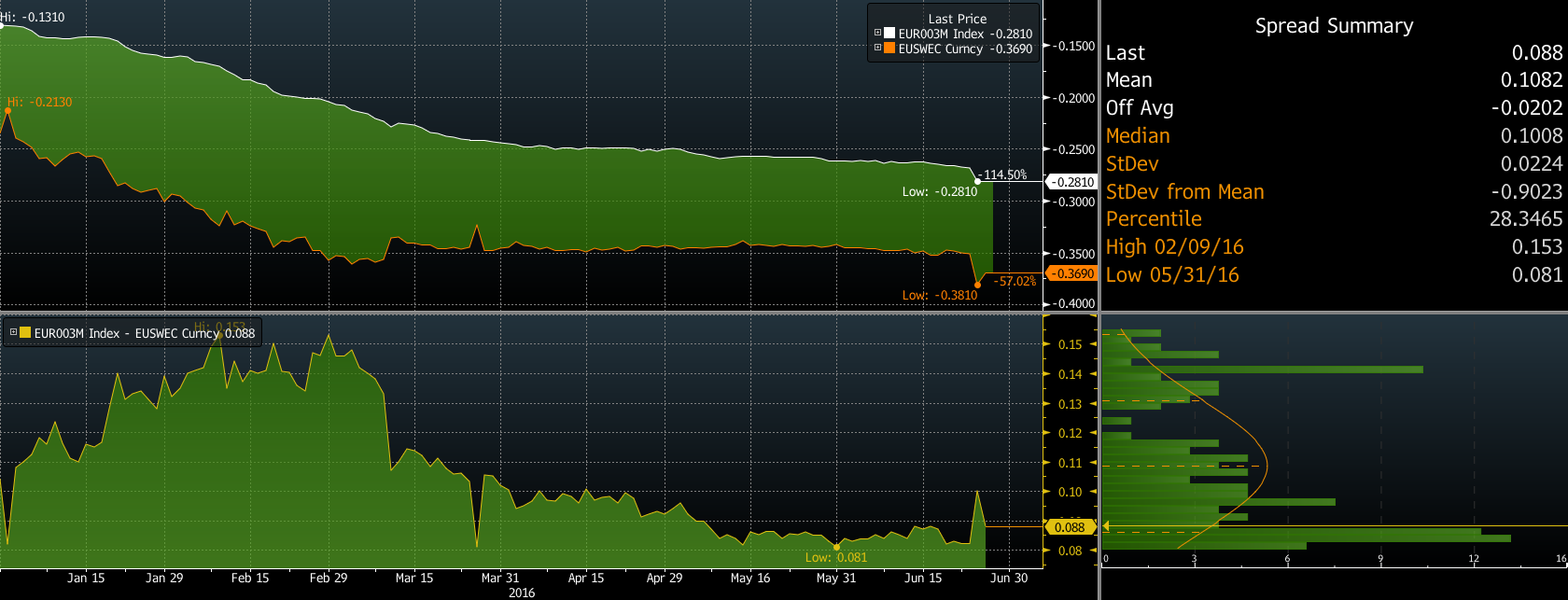

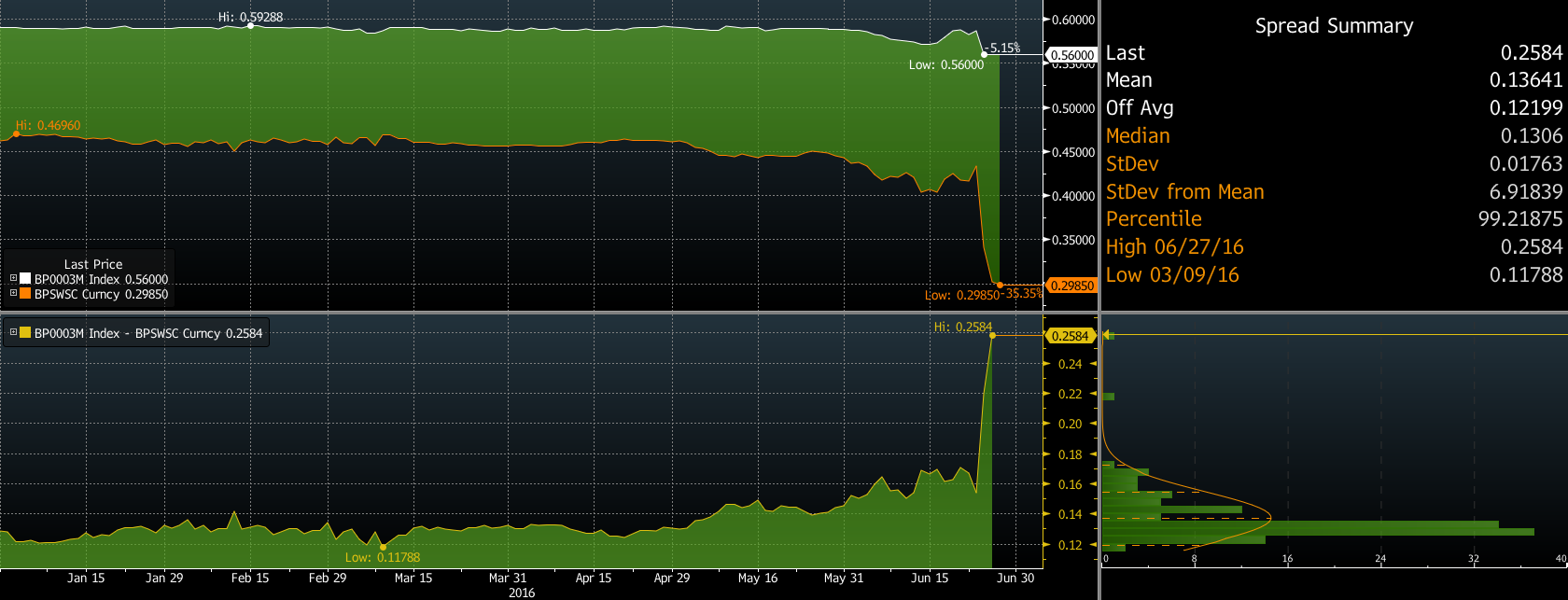

More importantly, I don’t see any systemic financial risk, as we had in 2008. One measure of financial risk is the LIBOR-OIS spread. It has ticked-up a few (2) basis points in Europe (1st graph below), a bit more (10 bps) in the UK (2nd graph), but nothing like we saw in 2008, when spreads blew out hundreds of basis points (3rd graph).

So far, then, I don’t expect much of a near-term economic impact from this vote, and I see the markets’ actions as orderly and logical. There is little risk of systemic default or liquidity freeze that threatens the normal functioning of the capital markets, à la 2008. But this does not mean that I think there are no tremors from the Brexit vote: the damage is political, and possibly severe.

Politics

Starting from the center and working out, UK politics are in turmoil. The ruling Conservatives had been split, with a small majority of MPs favoring to remain. The Prime Minister has resigned, and the party will now fight over his replacement (widely seen as the mercurial mayor of London, Boris Johnson). Virtually every (+90%) Labour MP favored (or, favoured) to remain, but the leader, the Marxist Jeremy Corbyn, was tepid in supporting Remain, his shadow cabinet has resigned, and Labour will now fight over it leadership. Unlike in the US, candidates for Prime Minister are chosen by party elites, not through direct elections. The third-largest party, the Scottish Nationals, are agitating for another swipe at independence from the rest of Britain, but the biggest (maybe only) winner is the fringe, far-right populists (bigots) of the UKIP.

Complicating political matters is a legal question: under whose authority can the UK invoke Article 50 of the Treaty of Rome (establishing the EU) to begin the process of exiting? Is the referendum sufficient? Or does it require an Act of Parliament? If the latter, the vast majority of MPs backed Remain, so it’s not clear such an Act would pass. New elections are likely, although even then it’s not clear a majority of Parliament would vote to exit the EU.

Whatever happens, British politics has been roiled. Most of London, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales voted to remain, as did most younger people. The Exit vote was carried by everyone else. Scotland has revived plans for another independence vote, and Northern Ireland has floated the idea of union with Ireland. Young people want to be able to backpack freely around Europe, and are waiting for the elderly, who voted to Leave, to die. The rest of England would be happy to see London engulfed in another Great Fire or bubonic plague. Don’t be misled by their quaint and proper accents: the British are at each other’s throats.

Article 50 of the Treaty of Rome spells out a two-year negotiation period for a member state to exit. Assuming a divorce agreement can even be reached, it then must be ratified unanimously by the remaining 27 countries. Good luck with that.

Some pundits (probably the same who called the vote so accurately) believe the EU will push for harsh conditions for a British exit, on the premise that the UK needs the EU more than the other way around, citing that 44% of UK exports go to the EU, whereas just 3% of EU exports go to the UK. But this argument overlooks the larger importance of Britain to the EU. It is the second-largest economy, after Germany, and has the largest military budget (3rd in the world, behind the US and China, ahead of Russia). The long-time sclerotic political dysfunction of the EU means it has had far less influence in global affairs than its economic size would dictate, but whatever influence it has comes largely from Britain’s power. An EU without Britain would lose most of whatever small sway it currently has in global affairs.

Beyond Britain, the Brexit vote will encourage the representatives of nativism, isolationism and protectionism. Already these forces represent a sizeable portion of the electorate in many European countries, as well as in the US. Regional fracturing may gather momentum, not just in Scotland, but in Catalonia and Basque in Spain, or Lombardy in northern Italy. A majority of voters in France and Italy want a referendum held on continued EU membership, and not so they can re-affirm it. A break by one of these countries would be much more complicated and would signal the definitive end of the EU.

So, politically, the Brexit vote is likely to have far-reaching consequences. A positive outcome might be for the EU to re-think radically its entire approach of ever-greater integration and regulation imposed by bureaucrats unelected and unresponsive to citizens’ needs and interests. That seems as likely as me becoming the next Prime Minister.

Investments

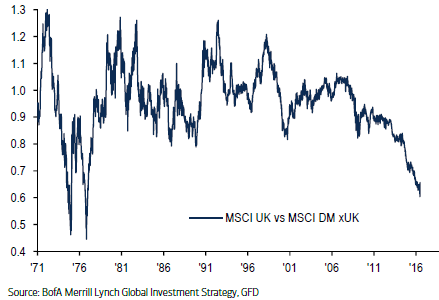

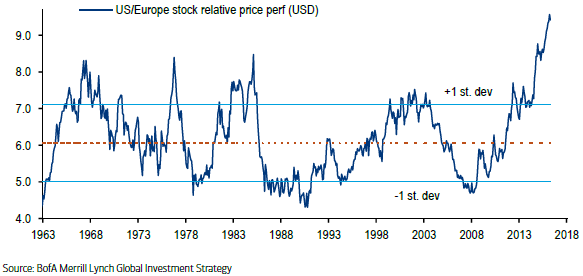

In my Inside the Triangle post (http://blog.angelesadvisors.com/2016/05/inside-the-triangle/), I laid out three angles to access the investment environment: sentiment, valuation and momentum. Well, sentiment and valuation have certainly deteriorated in the past few days (a good thing), but the trend is still lower, and whether your preferred analogy is a falling knife or a moving train, catching the former or standing in front of the latter is ill-advised. That knife (or train) is gathering momentum: UK stocks are at 40-year lows relative to the developed world (see first graph below), and US stocks are ahead of European stocks by the most since probably the 19th century (2nd graph below shows the past 60 years).

So, despite all the gut-wrenching, hair-tearing, clothes-rendering apocalyptic prognostications and market gyrations of the past few days, I’m reluctant to stray too far from our targets. Our model equity portfolios have been over-weighted to the US for some time, and I’m not looking to change that now. But the amount of relative US outperformance is at unprecedented levels. I prefer to wait for that trend to shift before moving aggressively away from the US, but I’m also cautious about raising the stakes further after this exceptional run.

Summary

I see the Brexit vote has having little economic impact in the near-term. The global financial system is not threatened by this vote, and the risks of a 2008 meltdown are zero (well, almost). Despite the heightened volatility and swift sell-offs, the markets are functioning rationally. The repercussions of Brexit are primarily political, and these are likely to be substantial, posing longer-term threats to the long-term integration of the world economy that has propelled billions out of poverty and enhanced the welfare of billions more. But those benefits, while widespread, have not been shared equally, and the political consequences of that have now been more clearly manifest.