Sunrise or Sunset: Thoughts on a Post-Pandemic World (Part 2)

In Part 1 (https://www.angelesinvestments.com/institutional-insights/sunrise-or-sunset-thoughts-on-a-post-pandemic-world-part-1), we outlined an economic backdrop of weak growth, high levels of government debt, cautious consumers, higher taxes and rising trade barriers. This is an unpropitious investment environment.

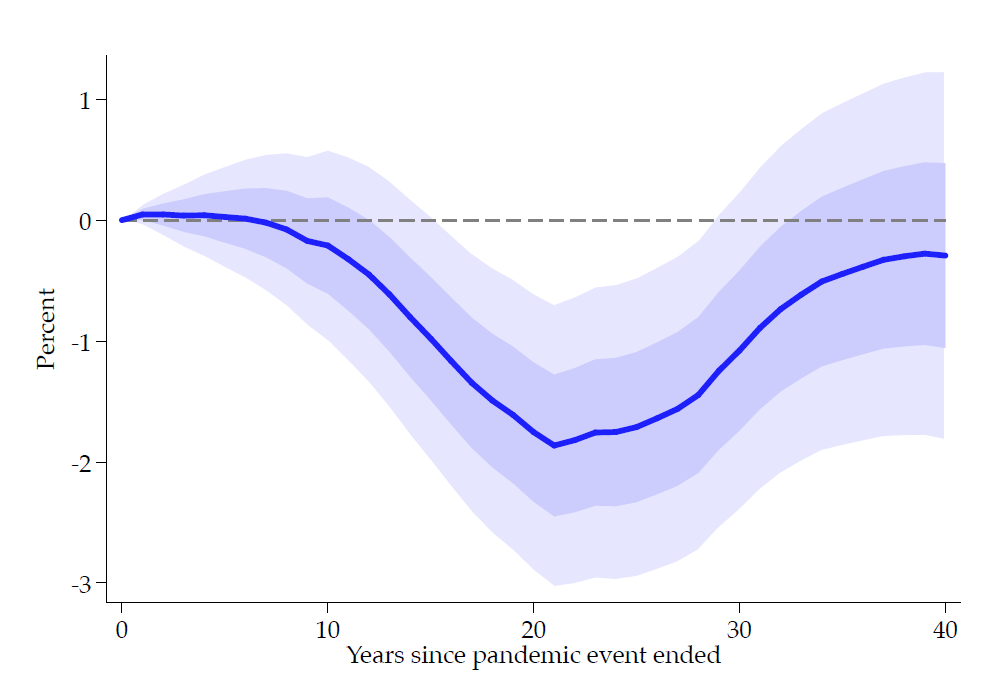

At a minimum, we can be confident that rates of return will be lower for a prolonged period of time. A study published by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (Jordà, Òscar, Sanjay R. Singh, Alan M. Taylor. 2020. “Longer-Run Economic Consequences of Pandemics,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2020-09) examined twelve major pandemics since the 14th century and found that “significant macroeconomic after-effects of the pandemics persist for about 40 years, with real rates of return substantially depressed.” (see chart below).

Response of European Real Natural Rate of Interest Following Pandemics

Source: Jordà, Òscar, Sanjay R. Singh, Alan M. Taylor. 2020. “Longer-Run Economic Consequences of Pandemics,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2020-09.

The authors speculate that principal reason for low rates of return for decades following pandemics is the propensity of households to increase savings, a phenomenon we identified in the previous section. In simplified supply-demand terms, excess capital (higher savings) in relation to investment opportunities lowers the rate of return.

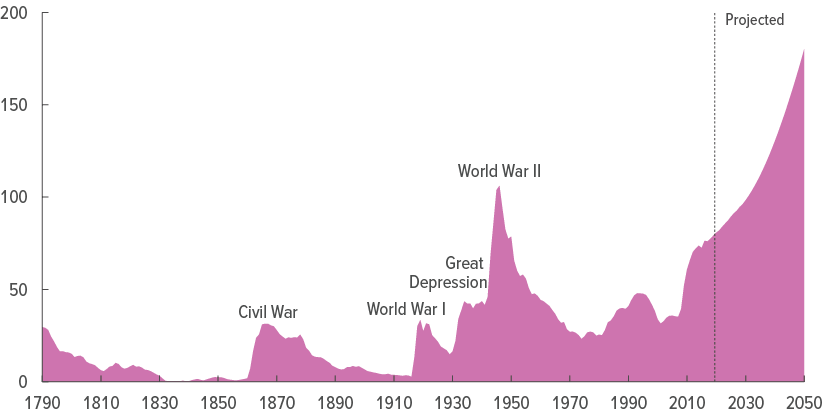

Another reason to expect low rates of return in the future is that government policies will demand it. Federal debt as percentage of GDP will soon exceed the high reached during the Second World War, accelerating well past that record in the years to come (see graph below).

Federal Debt Held by the Public as a Percentage of GDP, 1790-2050 (projected)

Source: Congressional Budget Office

Governments have three options to service/retire debt. Default is one, but is unnecessary in the US because debt is denominated in fiat currency, more of which can always be printed to repay debt. Default is often the only tool available to countries with foreign currency debt, but that does not apply to the United States. Secondly, higher taxes can be assessed to service/retire the debt, and this will no doubt occur. But with debt levels exceeding the size of the economy, it will be impossible to raise enough in taxes to have a meaningful impact. That doesn’t mean taxes won’t go up; they will. And so, finally, and most likely, is rate repression: creditors will bear the debt burden through negative real interest rates for years (more likely, decades) to come.

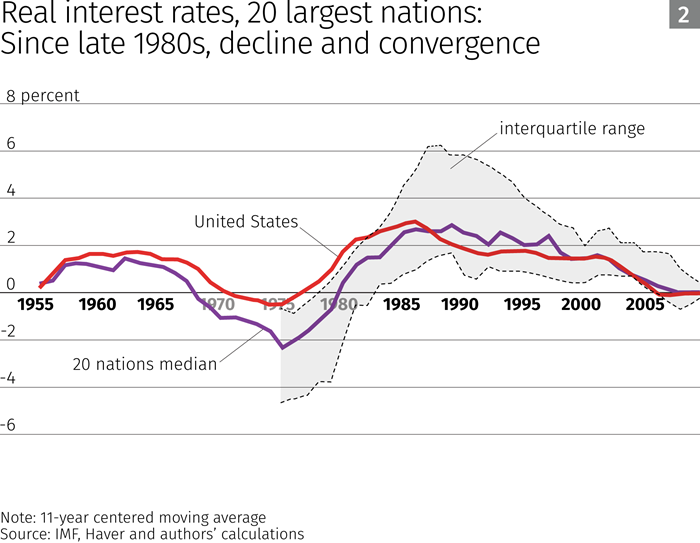

The last period of negative real rates was the inflationary 1970s (see graph below). But negative real rates can occur with modest levels of inflation. It’s just a matter of keeping nominal yields below the rate of inflation, and the Second World War period provides such an example.

Real Interest Rates, 20 Largest Economies, 1955-2015

Courtesy: Minneapolis Fed, https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2016/real-interest-rates-over-the-long-run

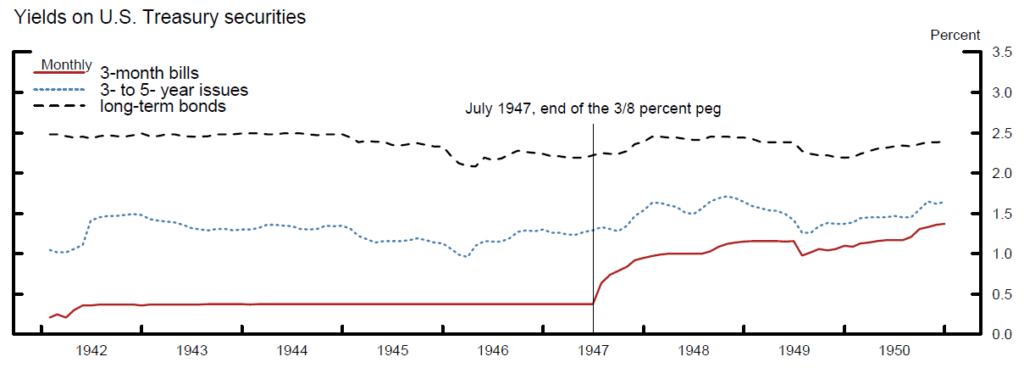

Short-term bill rates were pegged at 0.375% beginning in 1942, and long-term bond yields were capped at 2.5% (see graph below). Price caps during the war distorted reality for a time, but official inflation averaged around 3.5% in those years, modestly higher than the nominal rate investors earned on Treasuries. This rate repression was seen as necessary in order to finance the war effort. Following the war, price controls were lifted and inflation soared to 20%. The interest rate peg was allowed to drift modestly higher in 1947, but with inflation above 20%, yield curve targeting eventually became untenable and was abandoned in 1951, heralding the beginning of a thirty-year bear market in bonds that saw yields rise to more than 15% in 1981.

Yields on U.S. Treasury Securities, 1942-1951

Source: Carlson, Mark, Gauti Eggertsson, and Elmar Mertens, Federal Reserve Experiences with Very Low Interest Rates: Lessons Learned, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2008.

We won’t see 20% inflation in our future. Double-digit inflation was unleashed after a period of official price suppression, first during the Second World War and again in the 1970s (when President Nixon imposed wage and price controls in 1971. These were largely lifted by President Ford in 1974, and inflation reached over 14% by May 1980). Deflationary pressures, discussed in our previous section, are the more powerful force today. But nominal yields will likely be held below modest inflation, meaning that negative real rates is still a likely outcome for investors for the foreseeable future.

Government debt is an unattractive long-term investment (discussed in more detail below), but corporate debt looks more appealing. In 2019, US corporations spent more than $700 billion buying back stock and another $1.34 trillion in dividends. This $2 trillion was largely financed with $1.4 trillion of new debt issuance. Corporations have been leveraging their balance sheets. Capital investment, another potential uses of funds, has been moderate for the past decade, and a weak economic trajectory argues against higher capital spending in the future. We think this “sources and uses” of funds will shift, and we expect to see companies borrow less and divert marginal funds away from buybacks and dividends and toward debt servicing and repayment. Additionally, there are increasing political pressures to raise wages and avoid layoffs. Economic conditions and the political environment favor reducing corporate debt, a combination that is supportive for credit investors.

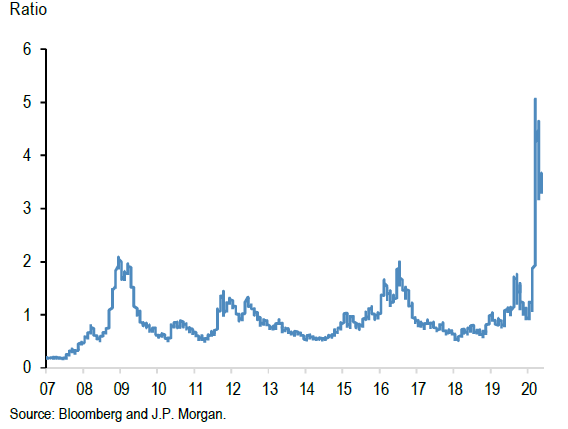

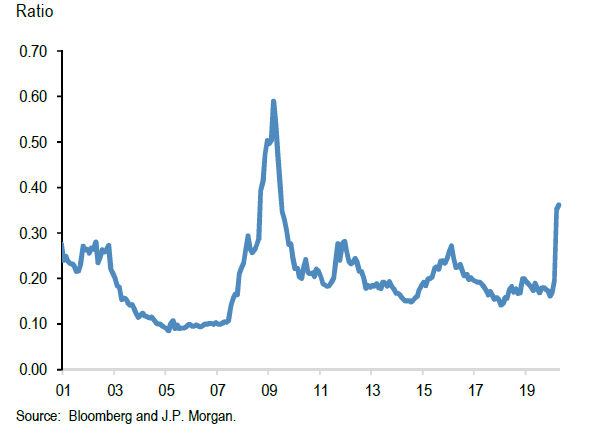

The recent sell-off in corporate debt, notwithstanding some rebound off the lows, has improved valuations, particularly relative to alternative investments. Spreads relative to government bonds (first graph below) and relative to equity earnings yields (second graph below) are at attractive levels.

Bloomberg Global Aggregate Corporate Bond Index OAS Relative to JP Morgan GBI Global Government Bond Index Yield, 2007-2020

Bloomberg Global Aggregate Corporate Bond Index OAS Relative to MSCI ACWI Index Forward Earnings Yield, 2001-2020

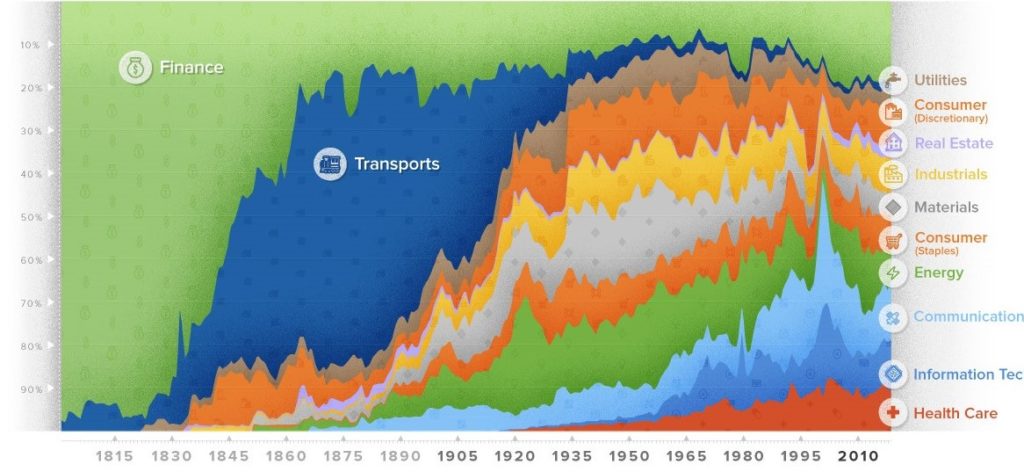

The prospect of lower overall growth, higher taxes and weaker profit margins does not auger well for stock markets, but it would be a mistake to abandon equities. Markets are dynamic, adapt to changes, as seen in the chart below. Finance and Transport dominated the equity market for its first hundred years. Energy and Materials were then the largest sectors for decades. Communications, Technology and Health Care are now growing in importance and are poised to lead in the future. Despite an overall challenging economic environment, there will certainly be companies and sectors that thrive and profit, offering scarce growth in a world bereft of it.

Sector Weights in US Stock Market History

Source: Visual Capitalist

Low rates of return are not only a challenge for most investors, it is an environment that calls into question traditional investment strategy. The challenge is that most investors have required rates of return that are higher than what may be available. For example, private foundations must (by law) spend 5% of their assets. If the foundation also wishes to protect the purchasing power of its corpus, it must earn this 5% in excess of inflation. Pension funds discount their liabilities at an assumed rate of return (around 7% for many), and if unable to achieve that hurdle will be unable to meet their future benefit obligations.

The average yield on the ten-year US Treasury note for the past 35 years has been 5%. So investors have been able to earn close to their required rate of return by owning safe, liquid Treasuries. Inflation averaged 2.6% p.a. over this time, so Treasuries provided a positive 2.4% yield over inflation. Today the yield on the ten-year note is 0.70%. The expected ten-year inflation rate is 1.2%, so ten-year Treasuries currently provide yield of 0.5% below the expected inflation for the next decade. A negative real yield is priced in Treasuries for the next 30 years.

Historically, investors owned Treasuries to earn a positive real yield for income and to provide protection in an equity market downturn. Real yields are negative, so there is an enormous opportunity (and real) cost to hold Treasuries for investors who must earn a positive return. Additionally, the fractional nominal yields provide little downside protection to a portfolio. For example, a rise of just 7% in the ten-year Treasury note would bring the nominal yield to zero. Assuming a zero-rate bound, this is all the appreciation an investor would receive in an equity market decline. To offset a 25% equity market decline, investors would have to allocate 78% to Treasuries, 22% to equities. No one would do this because the long-term expected return of that portfolio would be inadequate. In this example, equities would have to return more than 20% per year for a decade for that portfolio to achieve a 5% nominal annual return. That is not going to happen.

Long-term investors do have a potential advantage, an advantage, however, that is contingent on truly having a long-term view. This advantage emanates from the fact that standard errors of compound returns decline over time. This fact does not, in itself, improve returns, it only lowers the risk. But by reducing risk, investors are (or should be) able to hold riskier assets that will compound at higher rates of return. We say “should be” because holding riskier assets may (will) involve greater volatility in short periods of time, and many investors have innate behavioral biases to avoid declines in wealth, even if only temporary. The advantages of long-term investing accrue only to those who are truly long-term investors.

The investment period we expect, then, poses significant challenges for most investors. Earning an adequate return and constructing a diversified portfolio that offers protections from material short-term declines in wealth will be difficult. Traditional strategies will be insufficient in achieving either objective, and investors will need to alter, not only their allocations, but also their mindsets, to be successful.

The economic consequences of this pandemic we outlined in Part 1, and the investment implications we covered in this note, are considerable. As vast as these reverberations will be felt in economies and capital markets, a far more profound impact is likely to be manifested in politics and societies. We address that area Part 3.