Swiss Cheese

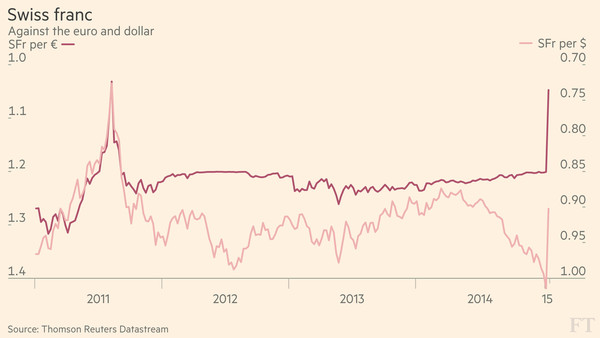

Back in 2011, as talk of the Eurozone disintegrating was at high pitch, investors fled to the perceived safety of the Swiss franc (CHF). Naturally, the value of the currency spiked higher, threatening the competitiveness of Swiss exports. So the Swiss National Bank (SNB-the country’s central bank) announced that it would sell an unlimited amount of Swiss francs at a rate of 1.20 per euro indefinitely, thereby effectively capping the value of the CHF.

For 3 1/2 years, investors exchanged their euros, rubles, florints or any other currency at this fixed rate, and the SNB accumulated these foreign reserves on its balance sheet. Despite the promise that the CHF would not appreciate, foreigners still wanted to hold the currency, and the SNB’s balance sheet doubled in size to more than 75% of Switzerland’s GDP (see graph below), more than twice the relative size of the Fed’s or Bank of England’s balance sheet.

As recently as last week, the SNB chairman, Thomas Jordan, reiterated the SNB’s firm commitment to maintaining the peg, calling it “absolutely essential.” It’s hard to know what turned something from “absolutely essential” last week to “unsustainable” and “unnecessary” this week, but the SNB announced last night that it was abandoning the peg. Simultaneously, in order to dissuade investors from buying CHF, the bank announced it was cutting overnight rates by 50 basis points, from -0.25% to -0.75%, and 3-month LIBOR by 100 basis points, from -0.25% to -1.25%. Yes, those are negative signs in front of those numbers.

It didn’t work: in seconds, the CHF jumped more than 30% versus the euro (see graph below) and Swiss stocks lost more than 14%, its biggest 1-day loss since the 1989 global meltdown. Nick Hayak, chairman of Swatch, called it a “tsunami” for the Swiss economy and its businesses. He is going to sell a lot fewer watches this year.

It’s hard to know the real reason for the SNB move. It may be that the SNB was getting less comfortable with the unlimited expansion of its balance sheet, and in particular, with its growing reserves of (likely) depreciating currencies. Perhaps it was tired of selling its currency at a discount to Russian kleptocrats moving their money out of rubles. Or maybe yesterday’s court ruling that permitted the ECB to begin buying government bonds was seen as leading to further euro weakness and therefore more flows into the CHF.

I don’t know what Chairman Jordan and his colleagues were thinking, but I take two broad messages from this action. The first is that no price can be pegged indefinitely, and the bigger the market, the sooner the peg will fail. Prices are determined by supply and demand, and governments can (and do) distort the pricing mechanism at their peril. Secondly, Europe is in trouble, on so many levels. Investors are eager to swap their euros for Swiss francs at a price 30% higher and a guarantee of a negative yield 100 basis points worse than yesterday. Wow.