Too Many Words

Among monetary economists, there is a raging debate over the merits of the Fed’s burgeoning balance sheet. Back in November 2010, an open letter to Fed chairman Ben Bernanke was published in the Wall Street Journal (http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2010/11/15/open-letter-to-ben-bernanke/), arguing that Quantitative Easing (QE) raised the risks of currency debasement and inflation. Some very smart economists signed on (Michael Boskin, Ronald McKinnon and John Taylor, all of Stanford), a few brilliant money managers (Cliff Asness of AQR, Seth Klarman of Baupost and Paul Singer of Elliott), and a couple of renowned historians (Niall Ferguson and Amity Schlaes), among others.

I did not sign the letter. I could say the reason was that I did not share the urgent fear others held of QE because I could see that these excess reserves would have little real impact unless they left the Fed’s balance sheet and flooded into the economy. With banks unwilling to lend and consumers unable to borrow, there was little chance these trillions of reserves would go anywhere or have any material impact. And with no requirement to manage the size of its balance sheet, the Fed could in theory expand it forever, or wind it down over a century, as it chose. I continue to believe that QE had very little real impact on the economy, benign or malign, and the end of QE and the prospects of monetary tightening need not be feared by investors.

All of the above is true, although I must admit, among friends, that the real reason I didn’t sign that letter was not disagreement and prescient foresight, but that simply, no one asked me. That’s not a complaint, just an admission.

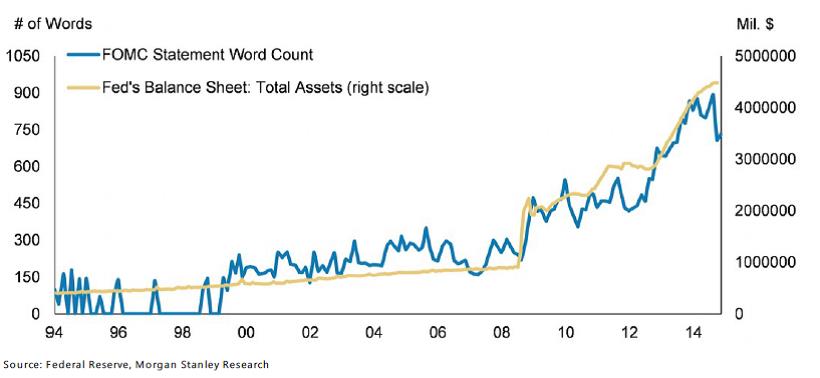

While I continue to believe that QE had little effect on the real economy, it apparently did have a pernicious (and unforeseen, by me, at least) impact on civility, specifically, the efficiency of language. For as the Fed’s balance sheet expands, so too does its verbiage explaining its decisions (kudos to Vincent Reinhart of Morgan Stanley for keeping tabs on this important data series). Clarity and succinctness have been under assault in our society for many years, and we must resist this rising tide of words. I am hopeful that the end of QE will facilitate the return to the good old days of 200 words or less from Fed pronouncements. If the authors will amend their 2010 letter to emphasize this point, I’ll happily sign it now.