-

-

-

![Michael Rosen]()

-

CIO Insights are written by Angeles' CIO Michael Rosen

Michael has more than 35 years experience as an institutional portfolio manager, investment strategist, trader and academic.

RSS: CIO Blog | All Media

Shock (Part 1)

Published: 11-22-2016

Shock, a sudden drop in blood flow, is a serious medical condition. Untreated, it can quickly be fatal. There are numerous types and causes of shock, including anaphylactic, an allergic reaction, cardiogenic, from heart damage, hypovolemic, from blood loss, and neurogenic, from spinal cord trauma.

The election of Donald J. Trump as President of the United States induced shock in virtually all of the people who did not vote for him, and probably even in many of the ones who did.

Thankfully, I am not a political pundit, which may now be the most disgraced profession in the country. But there’s no escaping having to make an assessment of the landscape for investors, as we must play the hand that we’ve been dealt. So I’ll try.

There are many possible paths of a Trump presidency: some hopeful, some benign, and others horrifying. The implications and consequences are far-reaching, affecting not only the economy, but politics, society, even the fabric of our country.

This will be a lengthy note (fair warning), so I’ll split it into parts. First, I’ll discuss the reactions in the markets, what investors are expecting (discounting) from a Trump economic agenda, and the economic consequences of possible policies. In the next note, I’ll focus on the investment implications of this possible agenda, with a focus on the new challenges to asset allocators. Lastly, I may venture into some of the broader areas of politics, where I am wholly unqualified to comment, but where the implications of a Trump presidency may be the most profound. Unless I first regain blood flow and come to my senses.

Markets Reaction

Markets reacted swiftly and dramatically to the election results. As a Trump victory was growing in likelihood that election night, stocks sold off 4-5%, first in Japan, the first major market to open, and again in the US futures market. This was consistent with all the prognosticators, who assumed the vast uncertainty brought by a Trump presidency would send equities sharply lower. But by the time the sun rose on the east coast of the United States, the futures market had largely recovered, and ended the day after the election more than 1% higher. In the following days, stocks continued to rise, but the bigger moves were seen in other markets: currencies, bonds and commodities. The US dollar (first chart, below) and bond yields (second chart, below) both soared to their highest levels in a year.

US Dollar Index, Last Twelve Months

US Government 10-Year Treasury Yield, Last Twelve Months

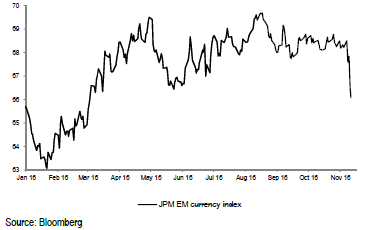

The dollar was strong against all currencies, although especially hit were emerging market currencies (JPM EM FX Index, graph below). Fears of protectionism harm the growth prospects for exporters, and a stronger dollar diverts capital flows, both bad news for emerging markets.

JPMorgan Emerging Market FX Index

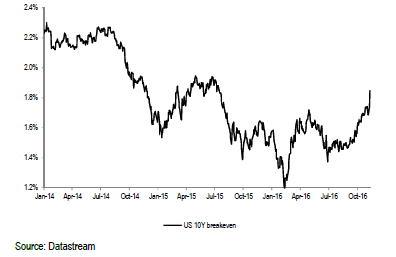

Bond yields jumped on fears of rising inflation (10-Year Breakeven Inflation, chart below). Inflation, and inflation expectations, have moved higher this year, and policies to restrict trade and expand government spending are likely to contribute to inflationary pressures.

US 10-Year Breakeven Inflation Rate

It may be premature to reach any conclusions about the effects of a Trump presidency, but the markets have moved, and I’ll try to interpret the rationale.

Trump Economic Agenda (Tentative)

As a candidate, Trump made numerous comments on economic policy that were, shall we say, often contradictory. Perhaps that’s not unusual for a politician. Nonetheless, there seems to be four broad areas of focus with meaningful economic consequences:

- Fiscal Policy: more government spending, especially in defense and infrastructure projects, and targeted tax cuts are the broad areas of emphasis.

- Trade Policy: reducing our trade deficit through the imposition of tariffs and/or renegotiating or reneging on existing treaties.

- Health Care: repealing the ACA, although possibly only parts of it, and replacing it with undefined policies affecting about one-eighth of the economy.

- Immigration: restricting new immigrants and deporting many who are now here.

Judging from the jump in equities and drop in bond prices, the markets are focused on the first item, fiscal policy. A sharp increase in government spending, financed with debt, along with cuts in tax rates, should provide a boost to near-term economic growth, and this seen as friendly to stocks, unfriendly to bonds. But, at the moment, markets are ignoring (or downplaying) the restrictive aspects of protectionism and lower immigration. As for health care reform, it’s impossible to know what will be kept and what will be scrapped. On the assumption that drug prices will be unchecked, the stocks of biotech companies jumped 9% the day after the election. Hospital stocks collapsed, on the assumption that enrollment in government insurance plans will be reversed, but hospital stocks have mostly recovered since. The impact of health care reform on the sector, much less in the broader economy, is impossible to know at this point.

So the near-term boost to the economy from fiscal spending and tax cuts may be partly (mostly?) offset by restrictions to growth from less trade and immigration. But look beyond the near-term effects and the favorable growth impact becomes less clear. And the positive impact to investors becomes even murkier.

Impact on Economic Growth and Inflation

A high level of sustained government spending is associated with slower economic growth, not faster, and with lower investment multiples. Europe is the case in point, with much higher levels of government spending than the US, much weaker growth, and much lower investment multiples.

The reason for the link between higher government spending and lower economic growth is the misallocation of capital. Certainly, some government spending is net additive, if invested in projects that return more than their cost of capital. GPS satellites, originally launched to guide intercontinental ballistic missiles, enable precision farming and keeps us all from getting lost, to name just two of the benefits. These are gains in efficiencies that well exceed the costs of the 31 satellites the US Air Force currently maintains. Expanding the capacity of ports, for example, could be another such project, unless, of course, other policies restrict trade, thereby negating the benefit of greater port capacity. But roads and bridges to nowhere get us nowhere, and however well-intentioned (or not), government spending is too often driven by political, not economic, considerations. Hence capital is often destroyed, economic growth is weaker, and investment multiples are lower when government spending is high.

Trump has criticized the Fed for putting excessive restrictions on banks (one reason bank stocks surged 14% in the days after the election) and for not pushing inflation higher. We know that higher inflation is bad for bondholders, but the market may be overlooking that high inflation is also bad for real economic growth. Perhaps too few investors remember the 1970s, with high inflation and weak real economic growth, but take a look around the world and tell me of a country with high inflation and strong real economic growth. [Go ahead, take your time.]

If the above is indeed the Trump agenda, and if indeed this agenda, or most of it, is enacted, we should expect to see higher inflation, higher interest rates, a stronger dollar, and a near-term boost to economic growth. These are the expected conditions that have pushed US stocks (especially, domestically-focused small caps), the dollar and industrial metals higher, with emerging markets assets and bond prices lower.

Higher inflation, higher interest rates and a stronger dollar all make sense in this economic environment, but sustaining stronger economic growth is problematic. Higher government spending and rising inflation are associated with lower, not higher, economic growth, as I noted above. The economy can be juiced for a time, but the underlying drivers of growth are population and productivity. Working-age (16-64) population growth in the US fell from 1.52% in 1998 to just 0.32% in 2016. Positively rapid relative to Europe, where working-age population growth went from 0.24% in 1998 to -0.53% this year. And productivity growth has been anemic. The 5-year annualized growth of productivity in the OECD (34 large industrial economies) was 1.67% in 1998, and just 0.49% today. Without faster population growth or gains in productivity, economies will struggle to grow.

Enough for now; in Part 2 I’ll look at some of the asset allocation challenges investors face.

Print this ArticleRelated Articles

-

![Not Beach Reading]() 6 Jul, 2018

6 Jul, 2018Not Beach Reading

I love the beach. And I read a lot. I like reading on the beach, but I am not a fan of beach reading. Beach reading is ...

-

![Dollar]() 6 Feb, 2015

6 Feb, 2015Dollar

My quarterly letter talks about the strength of the US dollar and why it should continue to rise (see Chart below), but ...

-

![Jolt]() 25 Aug, 2015

25 Aug, 2015Jolt

Two weeks ago (13 August, No Panic (Yet)) I noted that the renminbi devaluation was officially described as a modest ...

-