-

Still Beach Reading

-

-

![Michael Rosen]()

-

CIO Insights are written by Angeles' CIO Michael Rosen

Michael has more than 35 years experience as an institutional portfolio manager, investment strategist, trader and academic.

RSS: CIO Blog | All Media

Still Beach Reading

Published: 09-10-2020

It’s still beach weather here in Southern California, so I have a few more suggestions for beach reading.

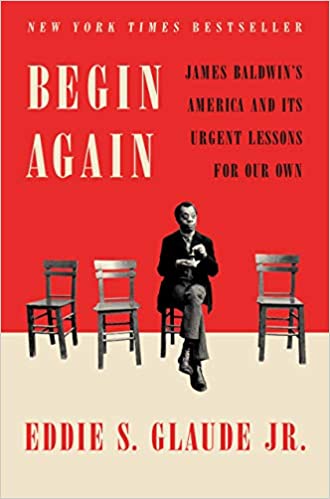

Begin Again by Eddie S. Glaude, Jr.

When I was in school, James Baldwin was unapproachable: his writing was nuanced and complex and personal. It was disturbing and incomprehensible to me. With the passage of a few decades, however, I have begun not only to appreciate Baldwin’s brilliance, but also to marvel at his relevance today. Eddie Glaude, a professor of history at Princeton, also avoided Baldwin, until graduate school, and he has been studying him for the past 30 years. This book is mostly a synopsis of Baldwin’s thinking, and how it evolved before, during, and after the civil rights movement. Glaude directly ties Baldwin’s words to today’s racial turmoil and challenges. Baldwin began in the 1950s trying to persuade the white majority to embrace black equality for their own sake and salvation. The assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. was an inflection point for Baldwin, and his later writing expressed more disillusionment. But Baldwin’s consistent message, through hope and despair, was that the fight for racial justice was never about laws and speeches, but about morality and love. I found some of Glaude’s opinions to be reductionist, for example, he characterizes Reagan’s victory over Carter in 1980 as white America’s repudiation of Black equality, whereas I saw it more as a repudiation of Carter’s incompetence. But Glaude shows us that Baldwin has never been more relevant and important than right now.

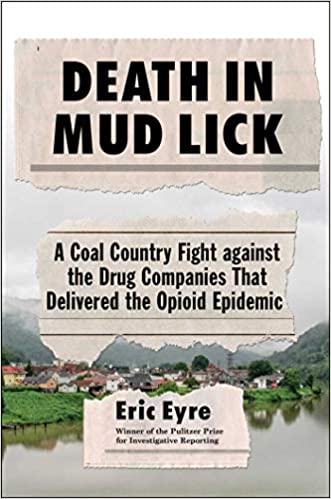

Death in Mud Lick by Eric Eyre

Eric Eyre won a Pulitzer for his reporting on the opioid epidemic in West Virginia, and this book is his full story. He presents the truly shocking statistics of abuse that befell these rural communities, and the criminal pursuit of profits and power engaged by drug manufacturers and (especially) distributors and their political allies. Along the way, Eyre describes the financial disaster that threatens his newspaper from forces beyond anyone’s control. His reporting almost single-handedly uncovered the causes of our opioid crisis, and reminds us of how invaluable an independent, local newspaper is to every community in America.

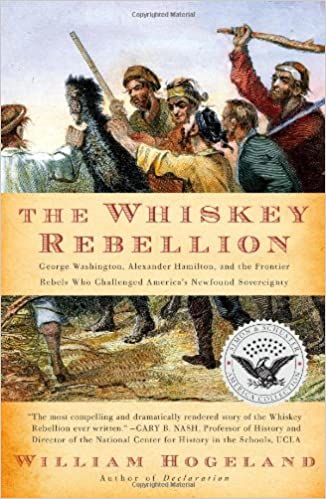

The Whiskey Rebellion by William Hogeland

The Whiskey Rebellion of 1791 was one of the (many) events glossed over in history books. If remembered at all, it’s probably that there were a group of bootleggers in the West who didn’t want to pay federal taxes on their moonshine, so George Washington led an army to put them in their place. But a closer examination reveals both the bigger picture of the rebellion and its particular complexities. For example, the excise tax was the brainchild of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, the key to his plan to assume the war debt of the states. Behind this was Robert Morris, the financier of the Revolution, who had bought up the heavily discounted bonds of the states and looked to be paid back at par (the Paul Singer of his day). Westerners could not transport their grain to the East as the bulk and poor roads made it unprofitable to do so. But converting grain into liquor made transportation economically viable, and also served as a currency in a wide region where coinage was scarce. Westerners saw this tax as targeting them, specifically, benefiting Eastern speculators at their expense. From this perspective, the Whiskey Rebellion takes on a much more important light in the early history of this country, and Hogeland does it justice.

Underworld, Don DeLillo

This massive (800 pages) novel was written more than 20 years ago, and I’m only now getting to it. It is an extraordinary on every level. It begins in the Polo Grounds, 1951, with Bobby Thomson’s famous home run, and then loosely follows that ball from out of the ballpark through various hands over the subsequent five decades. DeLillo captures the underside of America, from the Bronx to the Arizona desert, with both dignity and despair. The plot is secondary to the characters, their mundane and desperate and hopeful lives, with language that is colorful, profane and brilliant, not occasionally, but on every page. “She glided through the hotel lobby in high heels, like a B-movie actress awash in alimony and gin.” “They sat on the stoop drinking Old Mr. Boston, a rye whiskey unknown to the Cabots and Lodges.” There are hundreds more. It’s never too late to discover a masterpiece.

The Big Goodbye, Sam Wasson

“Chinatown” is one of the great movies ever made, and this book is a deep dive into its making through the perspective of four of its principals: actor Jack Nicholson, director Roman Polanski, screenwriter Robert Towne and producer Robert Evans. Each complex personality is well presented, but the great pleasure of this book is how each one perfected his craft, and how they collaborated (fought) to bring forth this film. It is also a look at how movies were made, with a particular focus on the many talented people behind the camera. Polanski emerges as the hero of this story, the driving force behind a convoluted script, a meddling producer and temperamental actors (some things never change). Ironically, and sadly for its creators, Chinatown was released the same year as The Godfather Part II, which (rightfully) swept the awards, save one, for best original screenplay. Wasson positions Chinatown at the moment of inflection of an industry pivoting from seeing itself as an art form to a purely commercial enterprise.

Print this ArticleRelated Articles

-

![Bring Home the Bacon]() 16 May, 2019

16 May, 2019Bring Home the Bacon

Bacon sure is popular. McDonalds, which probably has the best pulse on Americans culinary tastes, introduced Cheesy ...

-

![Old Age]() 16 Oct, 2014

16 Oct, 2014Old Age

Its been 3 years since US equities have corrected more than 10%. But theres no law about how long rallies can last ...

-

![Puerto Pobre]() 30 Jun, 2015

30 Jun, 2015Puerto Pobre

An honest politician may be oxymoronic (or is just moronic?), or maybe it's the black swan that surprises us when seen. ...

-