-

-

-

![Michael Rosen]()

-

CIO Insights are written by Angeles' CIO Michael Rosen

Michael has more than 35 years experience as an institutional portfolio manager, investment strategist, trader and academic.

RSS: CIO Blog | All Media

Sunrise or Sunset: Thoughts on a Post-Pandemic World (Part 1)

Published: 05-27-2020

Two and a half months of isolation engenders reflection, on what we’ve endured, and contemplation on what the future may hold.

Our reflections are incomplete, it’s still early, and our prognostications inadequate, as always. There is far more we miss and don’t comprehend than where we have clarity, and the future contains infinite possibilities rendering forecasts futile. Understanding comes only in hindsight, if it comes at all. Nonetheless, like a painting half-formed, we can begin to see shapes developing and can begin to speculate on where it is headed. This three-part series attempts to lay down our semi-cogent thoughts on this global pandemic and its implications.

Over the past decade, we encountered numerous “existential” threats to the world financial order:

- In 2011, (another) crisis of Greek government debt portended the collapse of the European Union;

- In late 2015, plunging oil prices wreaked havoc in the fast-growing energy sector, threatening to reverse the shift to energy independence;

- In early 2018, rising bond yields heralded a new era of inflation;

- In late 2018, the Fed’s non-response to weaker economic data and a burgeoning trade war presaged an end to economic expansion.

In hindsight, each of these events were mere blips in the longest bull market in history, although, at the time, all seemed to have had the potential to derail the economic recovery and reverse the markets’ substantial gains since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Our advice and positioning through all of these events was to stay the course, to be fully invested.

We characterized these incidents as only ripples in a long-term secular bull market, for example, we wrote in 2014:

https://www.angelesinvestments.com/insights/investment-insights/3rd-quarter-2014-plagueAnd again in 2018:

https://www.angelesinvestments.com/institutional-insights/breathe.At first, the COVID-19 virus appeared to be of a similar vein: a stone in the swift current of a secular bull market, causing turbulence that would shortly abate. That was my thinking as late as the end of February:

https://www.angelesinvestments.com/institutional-insights/put-down-the-gun.A week later, I changed my mind:

https://www.angelesinvestments.com/insights/videos/michael-rosen-on-bloomberg-tv-march-5th-2020:This was not a stone in the river, but potentially a Category 6 rapids [n.b.: the most dangerous river designation by the American Whitewater Association, where the consequences of error are severe and rescue may be impossible.] In other words, I had a sense that this global health crisis was not a perturbation, but a paradigmatic shift in the global economy with potentially profound sociopolitical consequences.

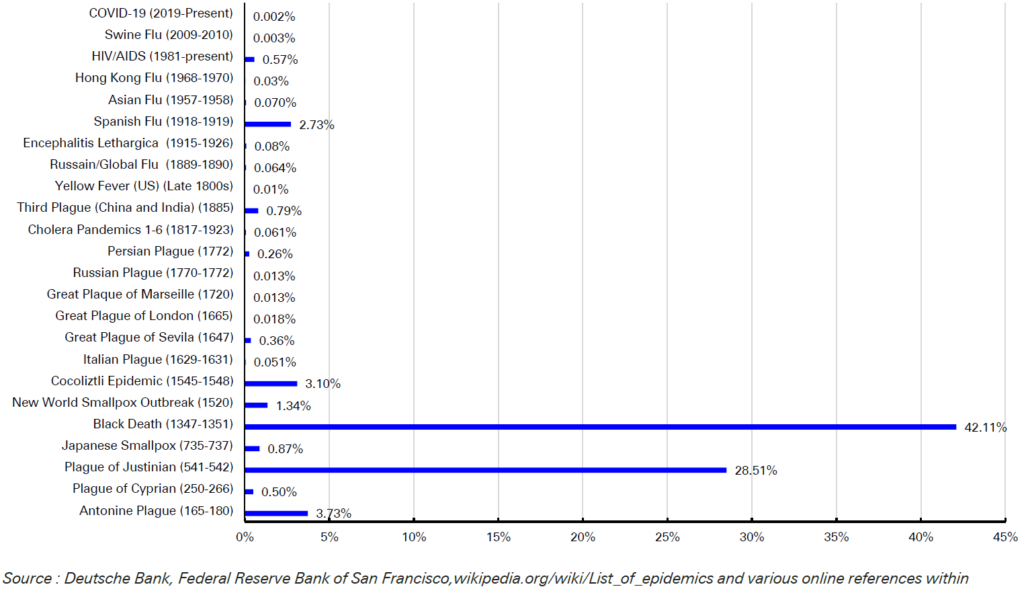

The First World War (and its subsequent influenza pandemic) ended the Victorian Era, reordering the world economy and demolishing the social mores of the previous century. That this pandemic, responsible for only a tiny fraction of the deaths from one hundred years before (and nothing like the Black Death of the 14th century—see chart below), would mark the breach of an old order to a new one was, is, hyperbole. And yet somehow this feels much bigger than a particularly bad, but semi-normal, flu season.

Estimated Total Deaths by Pandemic As a Percentage of the Global Population

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Wikipedia.org; Courtesy: Deutsche Bank

Reflecting on that moment of realization in early March of the momentous implications of these events, I find myself surprised. I cannot quite identify, much less articulate, why this moment felt different than previous periods of turmoil. But it did, and it does. On deeper reflection, perhaps we sensed for many years the pressures building, in our economies, our politics and in our societies. Tensions that were ultimately untenable and would one day snap. How and when were unknown, but we could feel it coming. I think that COVID-19 was the how and now was the when.

This crisis has exposed serious structural imbalances in our economies, in our societies and in our world, to which we cannot, should not and will not revert. Likewise, trends that previously were nascent or unnoticeable, have been accelerated and, in the aftermath of this pandemic, will dominate our lives more quickly than we expected. The implications and consequences are widespread and profound.

The future cannot be described; the possibilities are far too complex. But we can try to outline a framework, knowing it will be, at best, incomplete, and missing salient features, hoping, though, that we can fix our gaze in the general right direction.

We begin constructing our post-pandemic framework by assessing the economic outlook, then turn to the investment implications. Lastly, we examine some of the political and societal consequences of this extraordinary crisis.

Part One: Economic Outlook

The economic expansion that began in June 2009 and ended last quarter was not only the longest in US history at 129 months, it was also the weakest, with average annual GDP growth of just 2.3%. The next period of growth may or may not be as lengthy, but will almost certainly be weaker. Three principal factors will hinder economic growth for the foreseeable future.

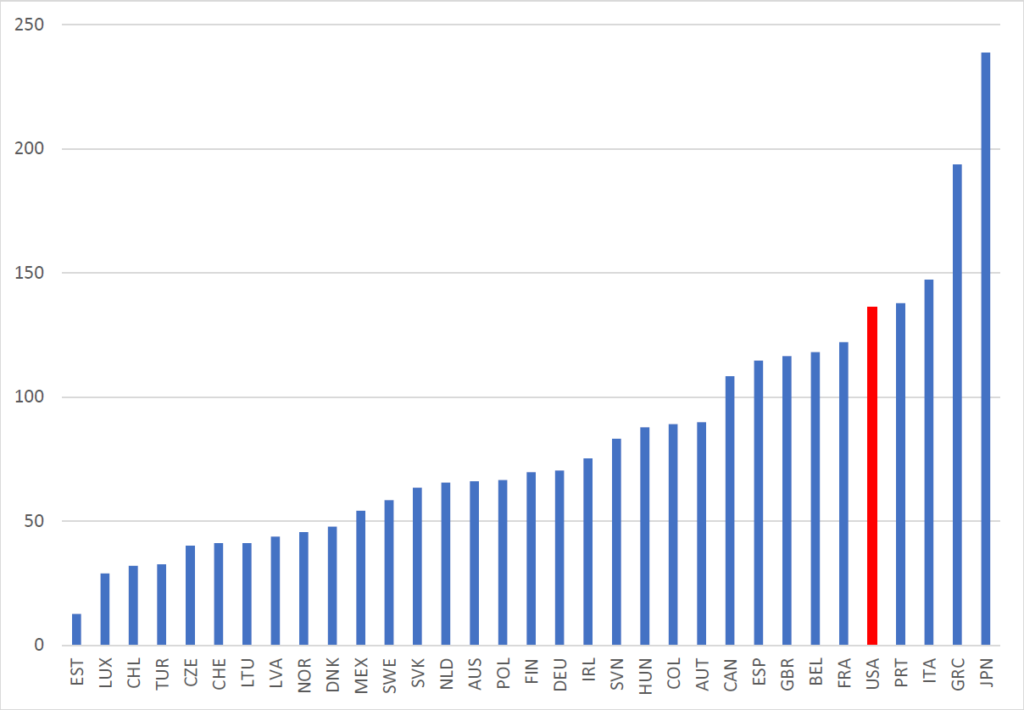

Public debt levels have surged in most economies at unprecedented speed and magnitude. The OECD forecasts government debt will rise $17 trillion this year, raising collective debt-to-GDP from 109% to 137%. The US exemplifies this development as a budget deficit of at least $4 trillion will raise debt levels 20% higher. That’s not quite Japan’s record level of debt-to-GDP, but it’s not far behind Italy (see chart below).

Debt as Percentage of GDP in OECD Countries

Source: OECD

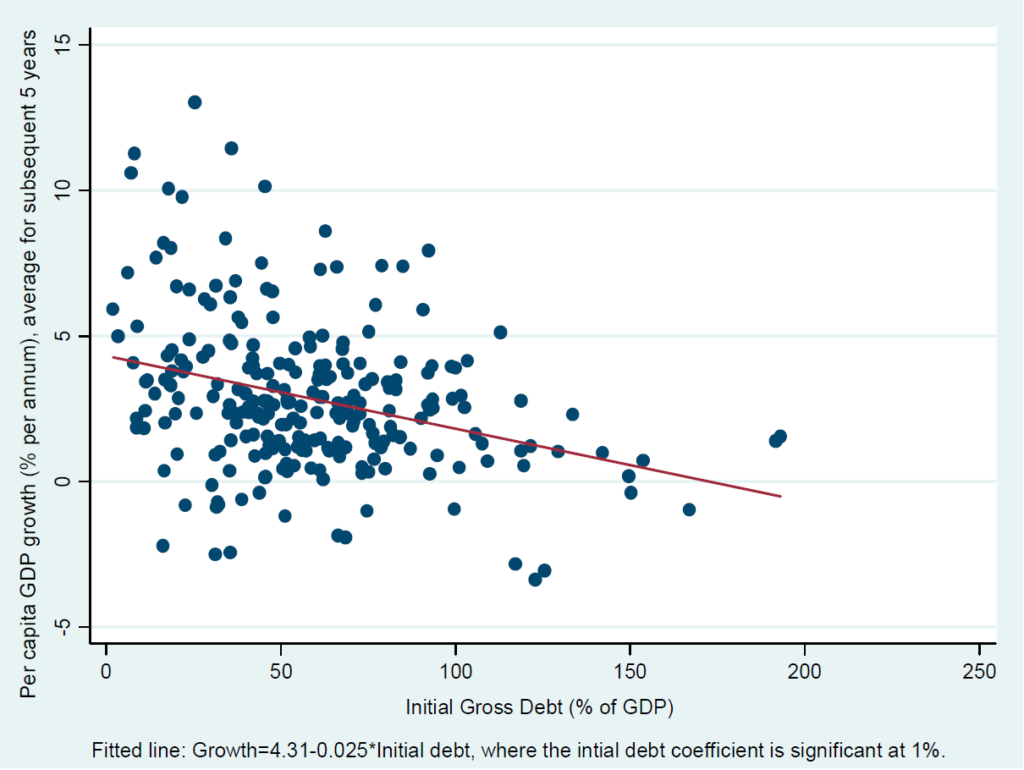

This matters because high levels of debt impede economic growth. A study of European economies by the European Central Bank (Checherita, Cristina and Philipp Rother, The Impact of High and Growing Government Debt on Economic Growth, Working Paper 1237, August 2010) found that economic growth slows measurably when public debt exceeds 90-100% of GDP. A broader study by the IMF (Kumar, Manmohan and Jaejoon Woo, Public Debt and Growth, IMF, July 2010) shows an inverse relationship between initial debt levels and subsequent economic growth, measuring a 0.2% drop in growth rates for each 10% increase in debt-to-GDP levels (see chart below).

Initial Debt and Subsequent Growth of Real Per Capita GDP

Source: Kumar, Manmohan and Jaejoon Woo, Public Debt and Growth, IMF, July 2010.

The empirical data are quite clear on the deleterious effect of high levels of debt on future growth. The reasons for this are harder to pin down, but studies point to falling productivity growth as a principal cause, reflecting a general reduction in investment.

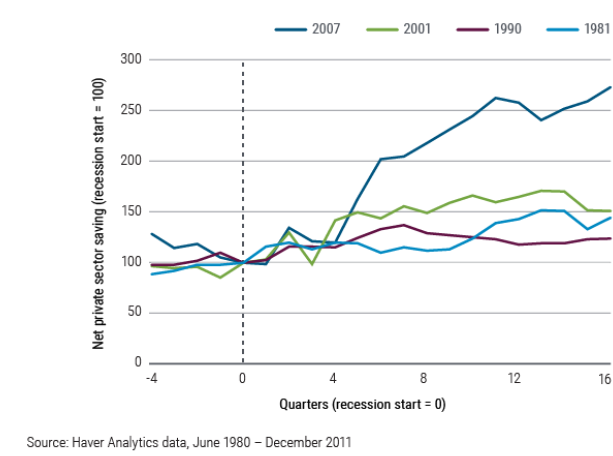

The second reason to expect slower economic growth is that household savings rates will rise, reflecting caution about future economic prospects. This was posited 200 years by David Ricardo (known as his Equivalence Theory), who suggested that as government debt levels rise, consumers will save more in anticipation of higher taxes and/or fewer benefits in the future. Regardless of the explanation, households have historically increased their savings rates following recessions (dramatically so post-2008—see graph below).

Net Private Sector Saving After Last Four Recessions

Courtesy: PIMCO

Rising government debt, falling productivity and investment, more savings and less consumption all have historical precedents, and all suggest sluggish economic growth ahead. The third factor that will lower the economic growth trajectory is de-globalization, a trend that has been building for a few years with escalating tariffs and trade tensions.

The world economy following the Second World War was driven by international trade. The value of exported goods rose to a record 26% of world GDP in 2008, fell and then recovered to 25% in 2011, and has been declining gradually since (see chart below). The last multi-year period of declining trade was in the 1930s, especially following the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, a major contributor to the Great Depression.

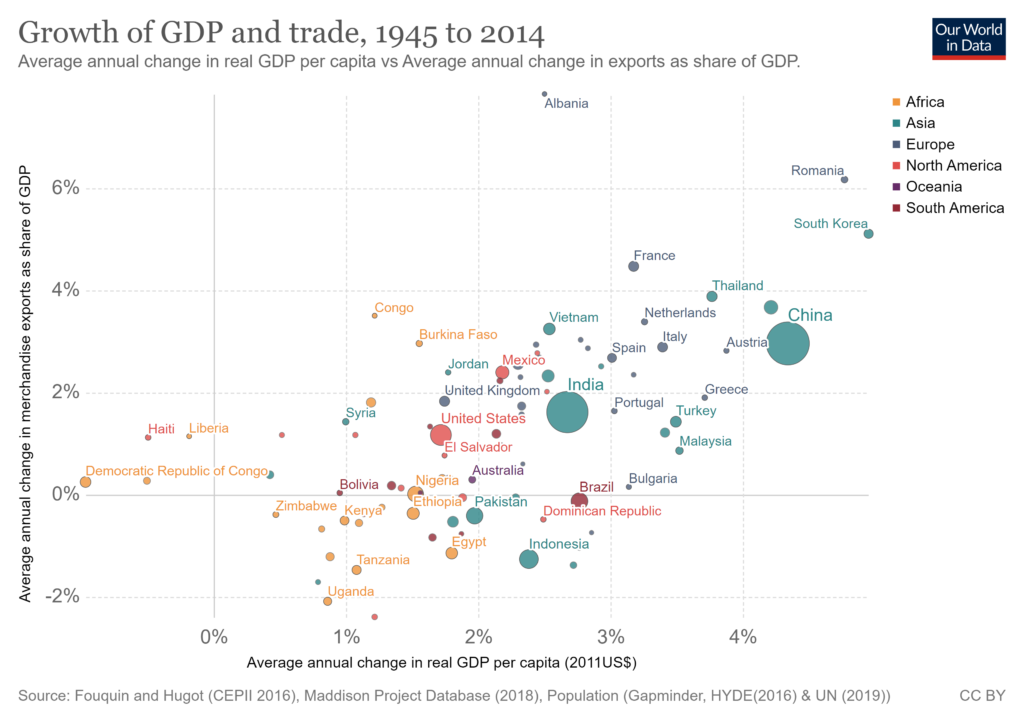

Trade raises economic growth and contributes to prosperity through higher productivity. The correlation between trade and economic growth is clear, as seen in the chart below.

David Ricardo (again!) established the “law” of comparative advantage, with the central concept of opportunity cost that drives gains in trade. More recently (1999), the seminal paper by Jeffrey Frankel and David Romer (Frankel, J. A., & Romer, D. H., Does trade cause growth?, American Economic Review, 89(3), 379-399) proved the causality effect trade has on economic growth. Subsequent research substantiates this conclusion.

Trade liberalization has been a principal factor in economic prosperity for decades and had enjoyed broad political support. That support is now seriously threatened with the rise of political populism on the right and on the left, marginalizing the once-dominant political center.

Trade brings efficiencies. But when shortages arise due to supply constraints and/or unanticipated surging demand, as we have seen in this current pandemic, the finely-tuned supply chains collapse, leaving countries vulnerable to urgently needed goods.

Trade is not the problem here. It is the dependence on single sources for supplies. If the entire production of a needed drug or piece of protective equipment were made at a single site domestically, there would still be shortages if that factory were not able to operate, for whatever reason. A recent study by economists at Michigan, Texas and Yale (Bonadio, B., Huo, Z., Levchenko, A., Pandalai-Nayar, N., Global Supply Chains in the Pandemic, May 2020) found that in a world without trade in inputs and final goods, the economic downturn due to the pandemic would have been marginally worse than it was as input sources are less diversified and still subject to interruption due to the pandemic. Eliminating trade in favor of domestic production does not increase security and is economically costly.

Still, it is likely that companies, and governments, will seek to diversify supply chains. The economy will lose some measure of efficiency, but it may gain in resiliency, and companies will seek the right balance between the two. Governments will be driven more by perceived political advantages in mandating sources of supply (re-shoring), and we may end up with policies that make the economy both less efficient and less resilient as a result.

Diversifying supply chains will be harder than passing a law. Priority should be given to emergency supplies, but a wholesale shift in supply chains will be difficult to achieve quickly. Approximately 20% of the value of imported goods required for domestic manufacturing in the US, Japan and Korea, for example, come from China, and relocating may be difficult. Apple, to take a specific example, has 14 of its 17 assembly plants located in China, and each one has a large ecosystem of sub-suppliers around it. There are compelling economic reasons for this, so moving away from China, which is certainly the political goal, will be difficult and expensive.

To summarize, future economic growth is almost certainly to be weaker than in the past, and this past period was the weakest (albeit the longest) on record. Consumers will be cautious in the face of uncertain prospects and in the anticipation of higher taxes to pay for burgeoning public debt. Trade, an engine of growth for the past 70 years, will continue to diminish. Supply chains will diversify, but some efficiencies will be lost.

This will be a challenging time for investors, a topic we turn to next.

Print this ArticleRelated Articles

-

![Path to Progress]() 8 Dec, 2015

8 Dec, 2015Path to Progress

Zimbabwe is a country of 14 million people. I've never been there, and I can't recall if I've ever met anyone from ...

-

![Beach Reading]() 11 Aug, 2020

11 Aug, 2020Beach Reading

One of the upsides to confinement over the past few months is that Ive been able to raise my reading capacity. Here are ...

-

![Floating Oil]() 24 May, 2016

24 May, 2016Floating Oil

Oil has had a nice recovery this year (see graph for Brent, YTD), up about 18% to over $48/barrel today. Of course, this ...

-