-

Chasing the Red Baron

-

-

![Michael Rosen]()

-

CIO Insights are written by Angeles' CIO Michael Rosen

Michael has more than 35 years experience as an institutional portfolio manager, investment strategist, trader and academic.

RSS: CIO Blog | All Media

Chasing the Red Baron

Published: 03-31-2017

You can’t eat relative returns is an old aphorism. It sounds like it could come out of Poor Richard’s Almanac (Benjamin Franklin), and I’m not really sure of its origin, but it means that we (investors) ought to be focused on the absolute growth of our money, not on its growth relative to some benchmark or peers. When we buy groceries (or make grants or award scholarships or cut pension checks), we spend (“eat”) actual dollars, not an amount relative to our performance against an index. Too often, we fall into the trap of trying to copy the strategies of high-performing peers, and inevitably fall short (how many investors adopted the “endowment model” in hopes of replicating Yale’s performance, only to fall well short?).

Still, we can’t help but compare ourselves to others; it’s in our nature. When focus groups are asked if they would prefer to make $80,000/year or $60,000, virtually everyone chooses the former. But when re-phrased as would you rather earn $80,000 knowing that your neighbors earned $100,000, or earn $60,000 when your neighbors made $50,000, studies showed a very strong preference for the latter. We choose to be poorer, in absolute terms, if we can be better off than our neighbors. I hope we understand that this is a sub-optimal choice.

Still, it is in our nature to crave recognition. Adam Smith, in Theory of Moral Sentiments, noted the human desire “to be observed, to be attended to, to be taken notice of with sympathy…and approbation.” For thousands of years we have created awards with artificial scarcity (“Athlete of the Year”, Congressional Medal of Honor, “Manager of the Year”) in hopes of promoting effort and energy toward a desirable goal. Encouraging such behaviors may spur superior results from some, but it may also cause others to take on more risks than they can handle. Studies have shown that the neighbors (!) of lottery winners spend much more on cars (conspicuous consumption) and have higher rates of bankruptcies. As Winston Churchill (who is endlessly quotable) noted, a “medal glitters, but it also casts a shadow.”

A recent paper* on aviation caught my attention (because it was about aviation). The authors, three distinguished professors from universities of Denmark, Zurich and Chicago, examined the records of more than 5,000 German pilots from the Second World War. In common usage, an “ace” is a pilot with five or more aerial victories. This has become a rare achievement: in the Vietnam War, for example, only two US pilots, Steve Ritchie of the Air Force and Duke Cunningham of the Navy, were aces (with five victories each). No American pilot has achieved that status since.

The most successful pilot of the First World War was Manfred von Richthofen, with 80 victories, forever immortalized as the Red Baron, Snoopy’s nemesis. But World War Two saw some pilots reach extraordinary heights (pun intended). In that war, 409 pilots had 40 or more victories, and the vast majority (379) were German. There were three factors that account for this preponderance of German success. First was that at the start of the war, German pilots were the only ones with actual combat experience, gained during the Spanish Civil War. Guernica, the title of Picasso’s most famous painting, was the first civilian town targeted for aerial destruction in history, carried out by the Luftwaffe. Secondly, most victories came against the Soviet Union, whose planes and pilots were generally both of abysmal quality. Lastly, the Germans had a rule, “fly till you die,” and unlike American crews who rotated out after 25 sorties, German pilots only stopped flying when they were shot down. This led to some impressive individual accomplishments. Hans-Joachim Marseille had 17 victories in a single day (1 September 1942), Emil Lang had 68 victories in one month (October 1943), and Erich Hartmann holds the all-time mark of 352 aerial victories (all but 7 against the Soviets). Hartmann’s last occurred hours before the war ended. His accomplishment is all the more remarkable because by May 1944, a full year before the end of the war, the Germans were losing 25% of their pilots each month.

Achievements were recognized by a mention in the daily armed forces bulletin (Wehrmachtbericht). This was considered a rare honor, reserved for spectacular accomplishments, and because it was broadcast to all forces everywhere each day, the honor was widely and instantaneously noted. To examine the impact these accolades had on other pilots, the researchers looked at the records of pilots who had previously been in the same squadron as the honored pilot, with the assumption that a prior personal contact or relationship with that pilot would likely provoke a greater motivation in other pilots. It turns out that it did.

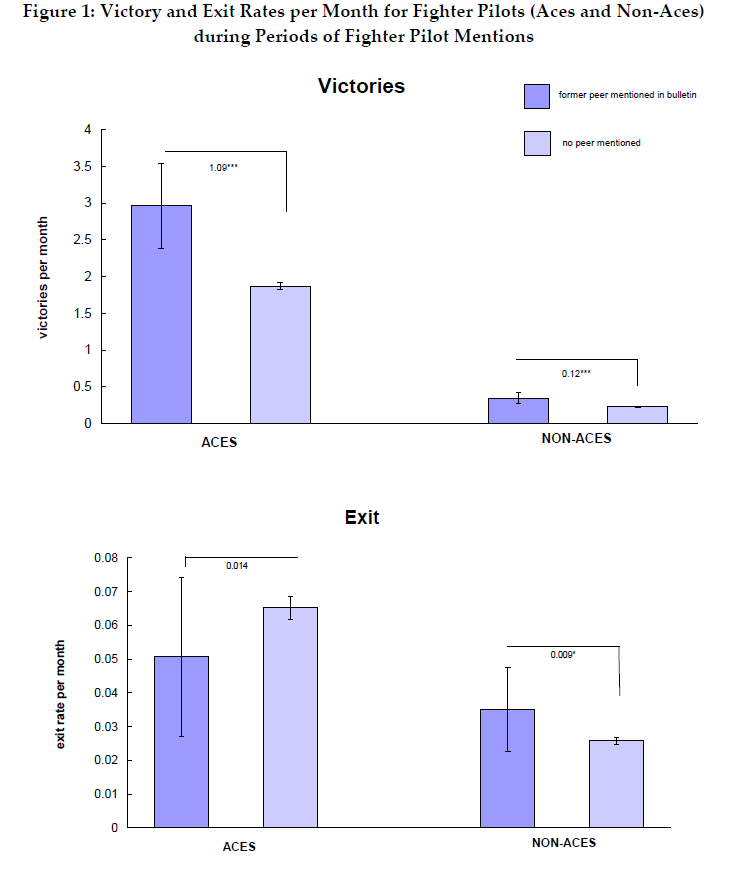

Researchers further grouped these other pilots by their previous records, with the top 20% called “aces” and the rest called “non-aces.” Figure 1 below shows the results in these two categories following a mention of a special achievement by a former flying colleague (“peer”). Victories for the top group increased significantly after hearing of a former mate’s accomplishments, from an average of 1.9 victories per month to 3.0 victories. The other 80% saw only a modest rise in victories, from 0.23 to 0.35 per month.

Remember, the only way for a German pilot to exit the ranks was to be shot down. Interestingly, the top group saw their “exit” rates decline from the baseline after a former colleague was honored. For the very best pilots then, the honoring of a former mate increased their subsequent victories and decreased their casualties. These highly skilled pilots were motivated to, and indeed did, perform better when seeing the accolades of a peer they knew. The less-skilled pilots were equally motivated, but lacking the skills of the best, did not fare as well. While their victory rate increased fractionally, their casualty, or exit, rates spiked (bottom panel). Their greater efforts resulted primarily in their higher deaths.

Relative performance against peers is a powerful motivational force. There is the anecdote that during the very crucial Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940, when the outcome very much hung in the balance, the top two German aces in that battle, Adolf Galland and Werner Mölders, were tied in victories when Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe, called Mölders to Berlin for consultation. Mölders protested that he would fall behind Galland, and consented only if Göring agreed to ground Galland for the three days Mölders was to be away. Amazingly, at that critical moment in battle, Göring agreed to pull his two top pilots from flying for three days.

So peer competition is a strong motivation. But fixating on our performance relative to peers may hinder our ability to achieve our own goals, and lead us to take unacceptable risks. For the few, highly skilled investors, competition may motivate us to achieve greater goals. For everyone else, taking greater risks will more likely lead not to more victories, but only to greater casualties.

*Philipp Ager, Leonardo Bursztyn, Hans-Joachim Voth, Killer Incentives: Status Competition and Pilot Performance during World War II, NBER Working Paper No. 22992, December 2016.

Print this ArticleRelated Articles

-

![MLPs]() 15 Oct, 2014

15 Oct, 2014MLPs

Some historical data from Credit Suisse below: MLPs are off 14% this month, pretty bad. Subsequent performance (no ...

-

![Stop the Game!]() 31 Jan, 2021

31 Jan, 2021Stop the Game!

Jesse Livermore was a legendary stock trader of the early 20th century. Mere rumors of his involvement in a stock could ...

-

![How The Mighty Fall]() 11 Nov, 2014

11 Nov, 2014How The Mighty Fall

Between March 2000 and October 2002, the NASDAQ Index fell 75%, from over 5,000 to under 1,300. Of course, valuations ...

-