-

-

-

![Michael Rosen]()

-

CIO Insights are written by Angeles' CIO Michael Rosen

Michael has more than 35 years experience as an institutional portfolio manager, investment strategist, trader and academic.

RSS: CIO Blog | All Media

Deflation? Not US

Published: 12-09-2014The dramatic (40%!) drop in oil prices has caused some hysteria in the media about the rising risks of deflation. After all, lower energy prices is deflationary. Well, that’s not quite true.

Inflation is a measure (imperfect, to be sure) of the general level of prices, not the relative price of one good versus another. If the price of steak rises relative to the price of chicken, people will consume less steak and more chicken. This has no impact on the overall price level in the economy. Likewise, the economy may spend less on energy, but then more on other stuff. The price of energy relative to everything else is falling, but that’s not the same thing as the prices of everything are falling.

No, the relative change in prices is simply a wealth transfer from one part of the economy to another, in this case, from energy producers to everyone else. It has no effect on overall prices.

This may be the most misunderstood economic concept, apparently, even among experts who should know better. Part of the confusion stems from the 1970s, when a huge spike in the price of oil was followed by rising inflation, leading many to assume the latter flowed from the former. Not so: the rising inflation of the 1970s was engineered by the Federal Reserve. The Fed believed (probably correctly) that the spike in oil prices in 1973-74 would cause an economic recession in the US, and thus they opened the monetary spigots, attempting to mask the rise in oil with a rise in overall prices. It was loose monetary policy that caused inflation to spike in the 1970s, not OPEC’s curtailment of oil. The spike in oil prices represented only a wealth transfer from consumers to OPEC, but instead of accepting this reality, the Fed’s misguided reaction was to pump more liquidity through the financial system. The result was the highest levels of inflation seen in US peacetime history.

Likewise, today’s drop in oil prices should be seen strictly as a wealth transfer from producers to consumers. That’s it. Now, of course, we will see CPI reported as a bit lower in the coming months, because consumers will, at first, save a portion of this windfall, but over time, spending will adjust and we’ll see CPI rise a bit more than it otherwise would. Unless, of course, the Fed changes course and decides to treat the temporary decline in reported CPI as a signal of deflation. That would be a mistake because (a) it is not a signal of deflation, as I just described, and (b) it would put the Fed further behind in normalizing monetary policy.

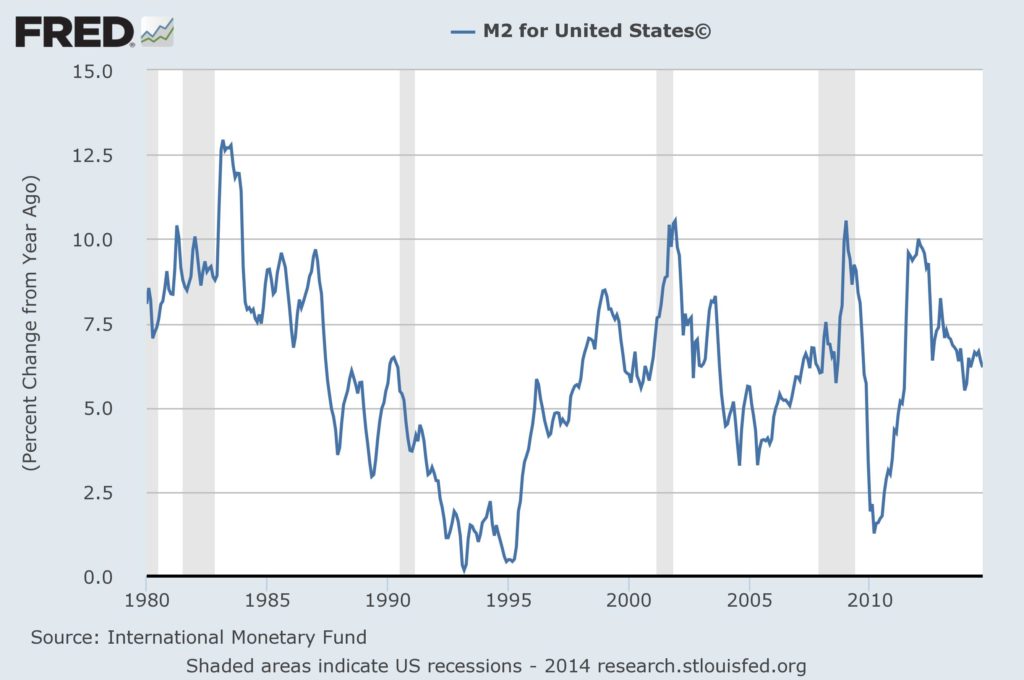

The Fed has done a pretty good job of navigating the economic shoals of the past 6 years: money supply is growing at a reasonable rate (see chart below), and interest rates are below the economy’s nominal growth rate, thus allowing incomes to grow faster than debt service and for balance sheets to de-lever.

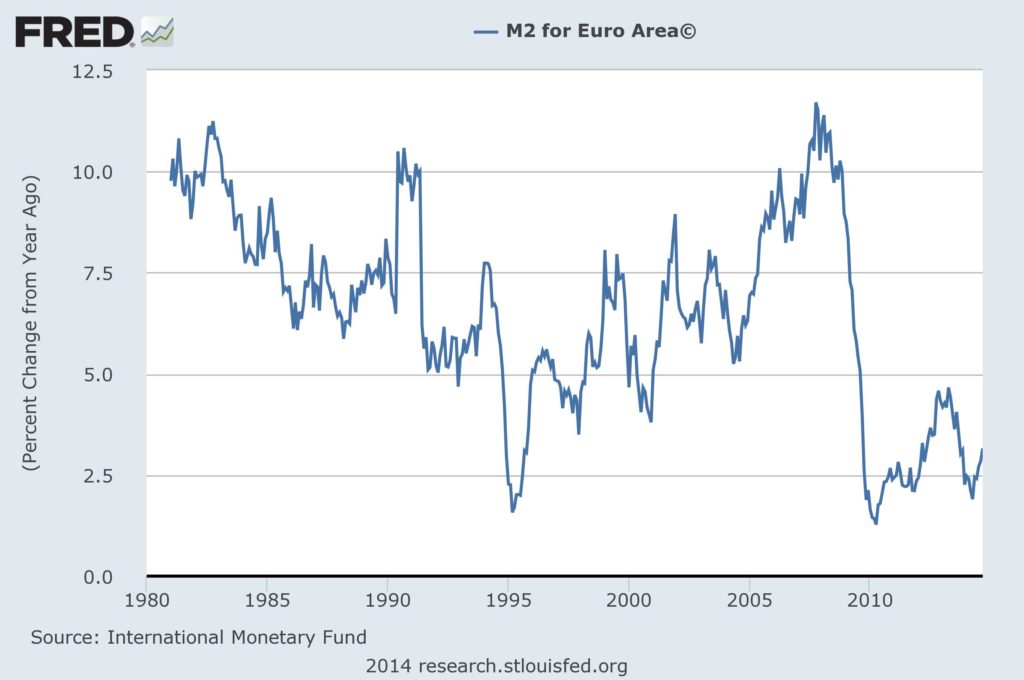

As long as these conditions continue, and that is what we expect, the “noise” about deflation in the US is only noise. The same cannot be said about Europe, however. The ECB has allowed money supply growth to shrink dangerously (see chart below), and while Signore Draghi has promised to accelerate the money supply, we haven’t seen that actually happen yet. Until he does, Europe’s risk of deflation will remain elevated.

Take a closer look at these two charts. M2 in the US is growing around 6%. Real GDP is up at 4%, inflation around 2%. In Europe, M2 growth is less than 3%, with real GDP a little over 1% and inflation around 1%. It’s not precise, but it’s no coincidence that these numbers (real GDP plus CPI ~= M2) add up.

So don’t be fooled by all the loose talk of oil prices and deflation. Deflation (like its cousin, inflation) is all about money, not oil (or cows, chickens or anything else).

Print this ArticleRelated Articles

-

![How The Mighty Fall]() 11 Nov, 2014

11 Nov, 2014How The Mighty Fall

Between March 2000 and October 2002, the NASDAQ Index fell 75%, from over 5,000 to under 1,300. Of course, valuations ...

-

![Petropolitics]() 2 Dec, 2014

2 Dec, 2014Petropolitics

For the past few years, oil has held steady at around $100/barrel, as supply and demand were largely held in check. ...

-

![Seven Lean Years? Done in Seven Minutes]() 30 Apr, 2015

30 Apr, 2015Seven Lean Years? Done in Seven Minutes

In Genesis (41:27), Joseph interprets Pharaoh's dream of 7 fat cows followed by 7 lean (and apparently, ugly) cows, as ...

-